On the first day of the bicentennial year (and 2 weeks before the grand opening of the Civic Center), Community Development Commissioner David Michel announced the construction of two pedestrian bridges to cross South Salina Street, one spanning the 400 block to connect Flah's and Dey's with Sibley's; the other crossing the 100 block between the Syracuse Mall and Vanderbilt Parking Garage. At a cost of $150,000 to $200,000 per bridge, Michel stated that urban renewal funds would be used to build the two city-owned skybridges. City councilors approved the project on March 9, 1976.

The inevitable accolades:

"If anything can attract shoppers downtown to revive South Salina Street, the two proposed pedestrian bridges will do the trick."—Donald O. Coverdell, president of Dey Brothers (quoted in Post-Standard, April 2, 1976)

"The bridges, providing easy access from one store to another and to parking garages, were considered by the councilors to be a step forward in updating downtown." (Post-Standard, March 22, 1976)

"The councilors voted unanimously on [the] projects, hailing especially the bridge construction plans as a 'shot in the arm' that downtown needs to put it back on its feet." (Post-Standard, March 9, 1976)

This, I suppose, is the history that some feel is best left forgotten, believing that revisiting this past somehow hinders the progress of Syracuse. And where would that leave us? Seeing the skybridge as one more urban renewal idea gone bad? Save for the giddy quotes above, it's not quite clear who ever thought the bridges were a good idea. Not the residents:

To the editor:

With the city administration begging for funds to reinforce our police and fire protection, now at their lowest efficiency, our Common Council gives its approval to bridges to Nowhere, across Salina Street. Regardless of this major boondoggle being financed by state or federal funding, it will rate with the Albany Mall and the Tower of Babel.

Having spent funds for tree planters, now extinct, and produced a Carnival on South Salina Street, poorly attended, both total losses, one wonders about the sanity of those proposing these Bridges of Sighs.

—John Gabor, Syracuse (Post-Standard, March 13, 1976)

Nor the Post-Standard editorial board:

But we can't help wondering, belatedly, just how two 8-feet-wide bridges pedestrian bridges over South Salina Street are going to boost the downtown economy.

Who needs the "north bridge" between the Syracuse Mall and the Vanderbilt parking garage at South Salina and East Washington Streets?

And how much will it help stores on either side of the 400 block of South Salina to have the "south bridge" connecting the Sibley city-owned garage with Dey's and Flah's stores?

There is such a span already over East Jefferson Street between the Marine Midland garage and Dey's, and we have been unable to learn it produces plus-business at either end. (Post-Standard, March 10, 1976)

Not even the mayor:

A $4,500 study of Syracuse's downtown, concentrating on methods of tying together stores, the Hotel Syracuse, and MONY plaza complex, was disclosed today by Mayor Lee Alexander.

Alexander revealed the new study to the Herald-Journal after ceremonies opening the new "Skybridge" connecting the Onondaga Savings Bank and Syracuse Mall buildings.

...

Mayor Alexander also indicated that such other pedestrian bridges may come for the downtown area. He said later that there are no definite plans for others, but that the Lebensold study will seek ways to tie together the business-hotel complex in the south end of the downtown area. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, October 15, 1976)

Fred Lebensold, architect of the Civic Center, had first been hired by the city four years earlier for SyracUSA plan, a $100,000 study commissioned by the Metropolitan Development Association aimed to revitalize Syracuse. The irony that Syracuse needed a plan to get out of ten years and tens of millions of dollars of renewal plans gone wrong was not lost on anyone, starting with Lebensold himself:

Lebensold, who helped in the rebuilding of European cities after World War II, pointed out, "Syracuse is the first city we know to have self-inflicted destruction. European cities rebuilt on the same patterns as before because Europeans are more conscious of traditions." He asked, "What do you do about preserving tradition?" Then he added, "Syracuse has more parking lots than I've seen in many cities. I'm not against cars, I drive one myself, but I walk to work." (Post-Standard, December 2, 1972)

Lebensold must have realized a city addicted to cars couldn't give up driving cold turkey, so he created a downtown plan that eased Syracusans into walking, with suggestions for a "pedestrian-oriented minibus" for all six blocks of downtown Salina Street, and to "favor the pedestrian by breakthroughs between adjacent stores and attractive weatherproof underground or overhead walks." (1972 SyracUSA plan). "Weatherproofing" the pedestrian experience seemed an appropriate step to take for a city that thought its residents had abandoned downtown in favor of suburban malls, and not because, say, these shoppers wished to avoid the sidewalk hazards alluded to by David Michel just twelve days after his skybridge construction announcement:

The dilemma: a temporary use for the football-sized field hole at the corner of Washington and South Salina Streets downtown.But move the pedestrians up from the sidewalk—away from the wooden fence in questionable condition ("Erwin Schultz, vice-president of the Chamber of Commerce, admitted he hadn't been to the site in a while...he wondered aloud about the condition of the wooden fence surrounding the South Salina Street side of the property. 'Maybe some art students could paint the fence,' he said.")—and that giant hole in the ground could become Syracuse's own Grand Canyon! Or, at least, not a literal death pit.

For three years the property has sat sleeping while the city has tried to find a commercial developer for the site.

...

David Michel, Commissioner of Commercial Development, of Syracuse, said talks are going on with the crater's next door neighbor, Syracuse Mall, to see if Mall developers might be interested in the spot either as a parking lot or landscaped park.

"To make the mall more accessible to the rest of downtown," Michel said.

The New York State Urban Development Corp. was originally contracted to find a developer for the site. The corporation went into default in February of 1974 and the city has been unable to locate a suitable developer since then, he explained.

Hopes for retail and office complex on the property have dimmed since "there's little demand for that right now," he said.

Even a single temporary site, such as a park, poses problems, he added.

"Who's going to maintain it? And what about security?" Michel said. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, January 12, 1976)

Which may explain why four years later, after more department store closings and suburban mall openings, the Downtown Syracuse Committee promoted the "forthcoming" skybridge system as a tourist and conventioneer attraction, encouraging visitors to explore Syracuse via habitrail:

We give high priority to the expansion of the skyway system, knowing that pedestrianization is an important key to renewed downtown vitality. Within the next few years, the five blocks of South Salina Street from the Syracuse Mall to Hotel Syracuse will be linked by interior skyways and pedestrian bridges across streets. The network will continue through the MONY office complex to the county Civic Center.

The bridges are an important element in the Hotel Syracuse expansion, which is scheduled to take place this year. The expansion will make Syracuse an even more attractive locale for conventions and tourism, which are so important to the local economy.—Raymond Hackbarth, chairman of the Downtown Syracuse Committee (Post-Standard, February 4, 1980)

Fifty years earlier, when streets were arguably far more hazardous for the pedestrian in downtown Syracuse—newspapers from the time abound with stories of men, women and children hit by trains, cars, streetcars, horses and wagons—the city of Syracuse promoted itself as a convention town due to its location at "the center of one of the most beautiful scenic areas in the United States." Visitors were encouraged to explore the area:

The trees line the streets in every direction. Practically every residential and a number of business streets are shaded by the most beautiful elms to be found on this continent. The vista down some of the residential streets, such as James, West Onondaga, East and West Genesee Streets and University Avenue is framed by an almost perfect Gothic Arch formed by the interlaced branches of ancient elms.

Beautiful parks are one of the greatest assets which a city may possess and Syracuse need not fear comparison with any other city in America. In addition to their natural beauty, these parks contain every feature for the recreation of the people, both winter and summer. Swimming pools, skating rinks, tennis courts, baseball diamonds, zoo and every other recreational facility are to be found amidst surroundings of great beauty. A trip through the park system of Syracuse will well repay the visitor.

Syracuse is provided with all the varied types of amusement features to be found in any large city. The Wieting is the legitimate playhouse and here will be found the same high-grade of those of any of the other larger cities. B.F. Keith's Theatre is one of the finest vaudeville theatres in the Keith chain, and the Temple Theatre plays vaudeville and burlesque. The principal downtown motion picture theatres are the Strand, Empire and Robbins-Eckel, which present first-run photo plays of the finest quality.

By 1981, the theaters had been razed for Sibley's and parking garages, dutch elm disease had reduced the number of elms in the city from 20,000 to 320 (Syracuse Herald-Journal, May 30, 1980) and the "six interurban electric lines radiating from Syracuse" were no longer available to take visitors to the parks located in neighborhoods that themselves had changed due to urban renewal. However, Downtown now had the Everson Museum, the Civic Center and a soon-to-be expanded Hotel Syracuse, prompting Mayor Lee Alexander to announce a new direction for downtown Syracuse:

Downtown, the mayor said, is in a transition period from a shopping and retail center to a banking, insurance, cultural and entertainment center. "There's no prime office space downtown," he said in explaining the changing climate downtown. He said empty store fronts downtown are the sign of a transitional phase of converting downtown from a shopping center into a center providing a variety of services. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, May 6, 1981)A moment of clarity: Syracuse realized that downtown could not compete with the suburbs, and decided to focus on its new and remaining cultural resources (the Landmark Theater had also recently reopened, thanks to volunteer efforts to save the former Loews). But before the summer fashions left the stores, the city reverted to its retail dreams a mere three months later when the developers for the Galleries came to town. However, in 1983, in line with Alexander's earlier declaration, an insurance company—Hartford Insurance—expressed an interest in moving into the former Syracuse Mall building (which closed in January 1982). The relocation became contingent upon the closure of the skybridge:

The firm plans to occupy 25,000 square feet of the floor, and the path of skybridge users through the floor to the stairway would bisect the office space. That creates a security problem, Atrium owners said.

At the time, the Galleries was nothing more than "Coming Soon" signs, and every month brought more retail closings. Yet when faced with a corporate business wanting to lease downtown office space, city councilors had but one concern on their mind:

Councilor-at-large Bernard Mahoney wondered if the city is completely abandoning the six-year old, $109,000 bridge, or if it can compel the Atrium to reopen it after a certain period of time.

"There is nothing in the agreement discussed with the corporation counsel that would mandate the reopening of the bridge," said attorney Raymond Hackbarth, representing the buildng's owners.

As Mr. Hackbarth had predicted three years earlier, skybridges had become central to the future of Syracuse, just not the way he had hoped. Except even he could not fully accept that this future growth of a business downtown meant permanent closure of the skybridge:

Conditions may change, and the firm may want the bridge open, Hackbarth said. In addition, he said, he has the idea the bridge could be moved. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, September 20, 1983)

And so it continued: the addition of a 20-25 story office tower to the Galleries project became "largely [dependent] on market conditions and the progress of the city's skybridge system." (Post-Standard, March 28, 1986). The original Convention Center envisioned "thousands of convention goers circulating among a ground of major downtown buildings connected by aesthetically pleasing, climate-controlled skybridges." (Syracuse Herald-Journal, October 4, 1989) In 1995, then-MDA Executive Vice President Irwin Davis—who had also been with the MDA at the time of the commissioned SyracUSA plan that promoted skybridges—stated "the Salt City would get a big boost from a coordinated skyway system":

"I've always been a proponent of them," he said. "They've been very, very successful in climates similar to our own. I only wish there was a way to link more of them." (Syracuse Herald-American, December 10, 1995)

How could a city dotted with closed and unused skybridges still contend that skybridges would be a "big boost" to downtown? Perhaps the same reason why Syracuse believed building the largest shopping mall in the country could change its destiny: Minneapolis.

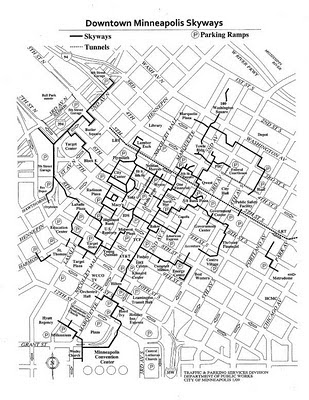

But even the thin-blooded can make themselves warm and happy in Minneapolis. Over the last 44 years, the city has tried to counter its five months of soul-numbing cold by erecting a game of architectural hopscotch that allows one to skip through town without risking even a wind-burned nose. Glass and metal bridges form "skyways" that allow pedestrians to traverse downtown in their T-shirts, if they so choose. The first skyway was built in 1962, across Sixth Street and Nicollet, with one end at the IDS Center, a shopping and office tower. Today, 63 bridges crisscross 72 blocks of downtown Minneapolis, making it the largest skyway system in the world, larger even than its counterpart in Calgary, Alberta, which covers 64 blocks. Businesses connected by the skyways co-own them, and most try for some originality in appearance, using multicolored glass and metal designs. (You can even go from the opera to the symphony and on to the Target Center without venturing outside.)

The skyways, which are either 12 feet wide by 12 feet high or 16 feet by 16 feet, link grand hotels, restaurants, high-end department stores, a Saturn dealership (at Marquette Avenue), businesses ranging from banks to baseball card and coin boutiques, and even the Hennepin County criminal courts (at Fourth Street). Inside, this Jetsons-like setting creates the surreal illusion of living — no matter the time of day or the wind chill — in a pleasant bubble equipped for almost all of life's exigencies. (New York Times, February 12, 2006)

In the 1990s, the Herald-American featured an article questioning why Syracuse couldn't replicate the Minneapolis skyway system:

The five-mile-long skyway systems of Minneapolis and St. Paul have changed Minnesotans' way of life by creating bustling, mall-like concourses that dominate that dominate the downtown culture.

And they're the envy of some Syracuse planners. (December 10, 1995)

Much as they had been the envy of 1970s-era Syracuse planners:

A trip a Syracuse delegation made a year or two ago to Minneapolis, which has pedestrian bridges, was said to have inspired the thought, "Why not Syracuse, too?" (Post-Standard, February 17, 1976)

Why not Syracuse too? Well, to begin with, the Minneapolis and St. Paul area has a population of approximately 2.8 million people. Minneapolis hosts professional football, basketball and baseball teams, not to mention over thirty downtown hotels, numerous retailers and light rail. A comparison of maps:

Simply put, Minneapolis and Syracuse are not the same size, nor in same competitive market for conventions or tourists. Unless, of course, Syracuse took a page from its 1926 convention booklet, and the city "most fortunate in being the center of one of the most beautiful scenic areas in the United States, an area which is devoted to year-round recreation" could rival the "land of 10,000 lakes" for outdoor enthusiasts. All of whom, I'm sure, would shake their head at this:

When Lynn Seppman moved to Minneapolis in 1973 and skyways were sparse, life was tough. In the winter, the computer consultant would eat lunch at his desk and try to bundle all his personal business on one day to limit his contact with the cold.

Twenty-two years later, a brilliantly sunny, autumn day with the temperature hovering around 50 degrees was "not quite nice enough to go out," admitted a shirtsleeved Seppman. (Syracuse Herald-American, December 10, 1995)

***

The downtown skybridges seem not so much a failed symbol of urban renewal or downtown revitalization, but rather, a living testament to Syracuse's confused relationship with the pedestrian. Placing a maze of bridges through a city seems to suggest that walking is drudgery, a necessity to get from one location to another in the few instances that you can't do so in the enclosed comfort of a car. They stand almost as an apology: "Sorry you have to walk; we'll make the environment as close to your car interior as possible." This isn't just Syracuse, but every American city that makes its civic and infrastructure decisions with its car-owning residents as the priority. What became of the idea of walking as discovery? Are the nostalgic memories that so often appear in the Post-Standard and Syracuse.com of places that skybridges and tunnels led, or of neighborhoods explored by a person's own two feet? How does one wander off the beaten path, when the path is an enclosure 8 feet wide and 14 feet above the ground?

Or, given their conspicuous start date during the ravaged days following urban renewal, might this have been the point? During the height of the urban renewal period, the city was not portrayed as a place where one would want to roam:

Putting himself in the shoes of a city employee, this Herald-Journal reporter went out looking at conditions in the city.

He expected to find the usual after-winter litter but he was amazed at the magnitude of the mess.

Much of the dirt is due to the many construction projects under way. Machines and trucks churn up tons of dirt every day, especially along Rte. 690 and 81 jobs.

But mud and dirt aren't the only offenders. I found literally tons of rubbish strewn on city streets ranging from scraps of paper to bottles and tree limbs.

West Street appeared to be a dumping ground of hundreds of beer cans, broken liquor bottles and tons of paper and dirt. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, March 31, 1967)

[One] disappointment is that the scarred area between the Public Safety building and the monstrous steam station must remain vacant, blighting the center of the so-called "urban renewal" area. Surely, some productive use of this parcel can be envisioned by the imaginative dreamers who demolished 100 acres of downtown with no real plan for replacement. At least they could plant some grass in the interim so that we native Syracusans need not turn our heads in disgust each time we pass this visual ruin.—Rudy Norman, Syracuse (letter to the editor, Post-Standard, July 6, 1967)

A decade later —and one month after the skybridge announcement—conditions didn't seem much improved, or at least not in the eyes of one 12-year old girl:

Dear city, and I mean the whole city,

My name is Joyce and I'm twelve years old. If I sound pretty tough in this letter, it's because I'm very concerned about our city and its future...

So I ask you to put this on the front page. I'm not just talking for us kids, but for the grownups too. Now you may have heard people saying downtown is going to the dumps, or how come everybody shops in the suburbs, says the downtown store owners.

Well, it's my turn to talk, and I say first of all to think about rehabilitating some of the dumpy looking buildings. People are always saying 'those were the good old days,' so why don't we fix up Loew's State Theater instead of building a new one and spending more money...

And fix up the old Chappell's store as bowling alleys with snack bars. And what about when people talk about air, water and land pollution, well did you ever hear of store pollution.

Well if you go downtown and look at some of those stores, they look like the city dump instead of a department store. But I admit they have done some good things to downtown. The only trouble is you have to go halfway through downtown to get to the good part. Some people might see the first part and turn back. I would...

Well if somebody with a lot of money cared about our city and used some of my ideas I think the people who live in the city would much rather go downtown to enjoy themselves than go to the suburbs.

...

Sincerely,

Joyce Pollastro, Syracuse

(from Syracuse Herald-American (front page of Metro section), February 8, 1976)

Did skybridges seem appealing not because of climate control, but aesthetic control? Did city leaders believe the carpeted floors and regulated environment of the mall could be replicated downtown via the enclosed walkways? The 2006 New York Times article about Minneapolis skyways certainly dispels this notion:

The skyways are not antiseptic. In winter, mangy street singers become mangy skyway singers, and police tell beggars to move along a block above street level.

Regardless the motivation, the truth remains that multiple times over the past three decades, when downtown Syracuse found itself at a crossroads, city planners sought a solution in skybridges spanning across streets. The lack of a sidewalk entrance to the built bridges suggests that these bridges were never constructed for safe crossing reasons; rather, they supposed that pedestrians would never be on the sidewalk in the first place. This effectively eliminated a staple of downtown retail vitality: window shopping.

So instead of shoveling the sidewalks and operating as though snow and cold were characteristic— and not flaws—of a walk through Syracuse, city leaders turned away from the one asset downtown still possessed—walkable density—and made a lazy attempt to mimic a city whose five miles of skyways would be the equivalent walking distance from downtown Syracuse to Barnes & Noble on Erie Boulevard in DeWitt. Granted, if you walked that distance in the snow and cold, along a route that Google Maps warns "may be missing sidewalks or pedestrian paths," you would be understood for wanting to make the return trip via enclosed comfort. Unfortunately, if you took the bus, you would have to cross Erie Boulevard, much like Syracuse University Professor Emeritus Joel Kidder did in December, 2009 when he was hit and killed by a car. An intersection where a pedestrian could really use a skybridge.