But what never gets old is the Syracuse response. John R. Searles, Jr., the executive vice-president of the Metropolitan Development Association, immediately penned a response to Huxtable and the New York Times (as printed in the Post-Standard, March 28, 1964). Rather than expressing anger or indignation at his city being called out as “ugly” in the nation’s premier newspaper, Searles essentially threw up his hands and agreed, the consequences of which Syracuse has been fighting back from ever since.

A breakdown of Mr. Searles’ letter (all emphases mine):

To The Editor of the New York Times:

Ada Louise Huxtable’s article in the Sunday Times, March 15, 1964, properly attacks the current ugliness of American cities, but does not mention efforts to probe the cause and find cures for the disease. In this she may give comfort to hand wringers and finger pointers who plead for historic preservation but hurt positive action programs which can actually preserve architectural assets and ally them “with the best new building.”

The “sick city” metaphor had been spreading through architecture and city planning circles since prior to World War II, comparing “blight” to decay and illness, and “open air” to cures. To be certain, the amount of sunlight necessary to disinfect the city wouldn’t be achieved by knocking down a few buildings in favor of pocket plazas; rather, massive amounts of land would have to be reclaimed. By the mid-1960s, architectural critics such as Huxtable and Jane Jacobs argued precisely the opposite:

To say that cities need high dwelling densities and high net ground coverages, as I am saying they do, is conventionally regarded as lower than taking sides with the man-eating shark. But things have changed since the days when Ebenezer Howard looked at the slums of London and concluded that to save the people, city life must be abandoned. Advances in fields less moribund than city planning and housing reform, fields such as medicine, sanitation and epidemiology, nutrition and labor legislation, have profoundly revolutionized dangerous and degrading conditions that were once inseparable from high-density city life (The Death and Life of Great American Cities, p. 218).

But Syracuse has often found itself stuck in a time warp, which is possibly why fifteen years after the James Street mansions initially met the wrecking ball and almost a quarter-century since the last streetcar ran in the city, Searles chalked up the ugliness to a byproduct of progress:

Most cities, like Syracuse, are making the traumatic adjustment from the street car to the automobile; from the pretentious mansion to the apartment and ranch house and from an economically dominant downtown core to a collection of shopping and commercial centers dispersed through an urbanized area. Syracuse in the last generation has also had to accommodate itself to the transformation of the New York Central right-of-way and the Erie Canal (both cutting through the center of town) into traffic arteries.

To meet these changes of the last 30 years, cities had no clear plans—and if they had plans—they had no legal powers to give effect to plans which might direct new construction and destruction towards more aesthetically pleasing results.

Of course, this didn’t stop Searles from arranging a two-and-a-half week tour of European countries for himself, Mayor Walsh, and seventeen other city notables (and their wives) for “city planning” services six months earlier!

The increase in automobile traffic and the loss of pedestrian traffic has had such a devastating effect on downtown property values that cities relying heavily for financial support on ad valorem real estate taxes have been understandably obsessed with the economic rather than the aesthetic effects of urban change.

How many cities can expect a Williamsburg treatment or have the opportunity to enjoy a Georgetown rehabilitation movement? Owners of obsolescent but historic property cannot be expected to let sentiment outweigh economic considerations for any substantial period of time. Children sell the family mansion when the land becomes more valuable as an apartment or office site than it could possibly be worth with the old house—heavily taxed and expensive to maintain—undemolished.

Interestingly enough, while we have come to associate urban renewal with the destruction of the historic 15th Ward, Searles seems clearly focused on the James Street transformation. Hardly surprising given that Searles and Mayor Walsh decided to tour Europe when hundreds were picketing City Hall in support of the residents of the 15th Ward, but a bit of a head-scratcher when you consider this: there was little to no organized public support for the historic preservation of the James Street mansions:

If the 2000 persons who roamed through the old Gen. Elias W. Leavenworth mansion at 607 James Street could have displayed the same interest a few months back as they did yesterday, then the remains of one of the last of Syracuse's historical landmarks yesterday might not have been picked over, inspected closely, fondled gingerly by those prideful of their city's past or disdained by a handful seeking just practical usage of the old items. (Post-Standard, May 16, 1950)

Also puzzling is Searles’ reference to Georgetown, as their residents were successful in saving endangered historic architecture by precisely focusing on the economic value of the buildings:

Historic Georgetown, Inc., in Washington, D.C. successfully bought and rehabilitated several outstanding examples of mid-eighteenth century architecture at 30th and M Streets in that city. In 1951, the houses were about to be torn down to build a parking lot. To save these buildings, a group of Georgetown residents formed Historic Georgetown, Inc. The aim of the corporation was to make not only a sound architectural restoration but also a sound business achievement. Money was raised by the sale of stock to Georgetown residents and a plan was worked out whereby subscribers might donate their stock to the National Trust and take a tax deduction for this gift at par value. As a result, the National Trust is now the largest single stockholder in the corporation. The restoration of these buildings is now complete except for one small apartment. The completed part is fully occupied on long-term leases and the rentals provide a sizeable surplus above upkeep, taxes, interest and preferred dividends. The operations of the corporation are deemed locally to be quite successful (College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal, Providence City Plan Commission, 1967, p. 13).

Yet Searles was very familiar with the area, as prior to his position as chief executive of the Metropolitan Development Association, Searles had worked as executive director of the Redevelopment Land Agency in Washington, D.C. for from 1951-1961, where he oversaw the “redevelopment” of Southwest Washington:

Inspired by the resurgent downtowns he had seen emerging from European cities damaged in World War II, Mr. Searles sought to bring a similar spirit of modernism to Washington...From 1954 to 1960, the old rowhouses and alleyways of Southwest were demolished, along with hundreds of small businesses. About 20,000 residents, most of them African American, were forced to find new homes.

The best current solution and indeed perhaps the only solution of general availability is urban renewal. The acquisition of obsolete blighted property and resale subject to conditions of preservation and architectural standards is making possible the retention of many fine old buildings. The use of renewal to study and preserve structures in the College Hill area in Providence is an outstanding example.

Searles is referring to the 1959 study conducted by the Providence City Plan Commission which proposed the use of federal Urban Renewal funds not to raze the historic buildings of College Hill but—gasp!—restore and renew.

A number of architecturally significant structures in Southwest Washington which were surrounded by slums and inadequately maintained are being brought back to life through urban renewal. Wheat Row, built by Lawrence Washington, George's brother, the Washington, Lee and Barney Houses are being integrated in Architect Clothiel Woodward Smith's design for the Harbour Square apartments.. The Law House to the north of N Street S.W. was required to be preserved in the Tiber Island Development. Both preservations were accomplished through urban renewal.

The best opportunity for Syracusans to save the Third Onondaga Court House is through urban renewal. There is no current apparent economic use and developers seeking the building as a parking lot gain support with offers of taxes for currently public property. They are held off only by a group led by Common Council Majority Leader Albert Orenstein, who has a considerable following in his efforts to solve a very difficult problem. Local citizen efforts saved the Weighlock Building on the old Erie Canal. The Syracuse Savings Bank has made an "uneconomic" investment in the' preservation of its local building.

The difference between Providence’s College Hill plan and Searles’ self-congratulatory Washington references—and stated plans for Syracuse—is that Providence aimed to preserve not a mere building or two, but the entire neighborhood:

Unfortunately, the approach in most cities has been piecemeal, and except in a few instances, only one or two of the techniques described in this report are in operation at any one time in a locality. The comprehensive approach to renewal of a historic area is needed and the techniques described in this report may guide the way for such renewal in College Hill and in other parts of the country. (College Hill: A Demonstration Study of Historic Area Renewal, Providence City Plan Commission, 1967, p.13)(Granted, it should probably be noted that a mere two years after publishing this report, the Providence City Plan Commission published an urban renewal plan for Downtown Providence not much different than Syracuse’s own, yet never materialized due to lack of interest.)

A total downtown urban renewal plan now underway has among its objectives one of saving the best of the old architecture not only for sentiment or to blend, but also to influence and to guide the design of new buildings. Syracuse would be vain to aspire to become a Paris or Vienna, but it is proud and becoming increasingly sensitive about its appearance.

Syracuse could never aspire to be a Paris or Vienna, yet Searles organized three additional trips to Europe after the initial 1963 excursion for himself and the city VIPs, in the continued name of city planning!

Similarly, from Searles’ 2005 Washington Post obituary:

Writing in The Post, Mr. Searles extolled the parks of Copenhagen and the vibrant urban dynamism of Rotterdam, but that rosy vision of Southwest Washington never developed. Instead, it remained largely desolate until highways, large office buildings and apartment houses were built in the 1960s and 1970s.We agree with Miss Huxtable’s estimate of the significance of the Council on the Arts’ excellent study, but disagree strongly that "most urban renewal seems doomed to sterility.” Rather, cities which like Syracuse, wish to use their excellent old buildings as the cornerstones of reconstruction, will find urban renewal to be their best and perhaps only solution.

JOHN R. SEARLES JR.,

Executive Vice President.

Metropolitan Development Associationof Syracuse and Onondaga County

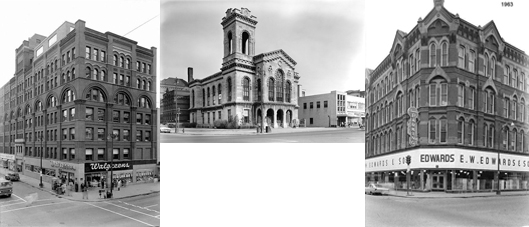

Just a few of the “excellent old buildings” that didn’t make the “best of the old architecture” cut:

|

| From left: McCarthy Warehouse, Third Onondaga County Courthouse, Kirk Fireproof Building |

And their replacements:

***

Which brings us to the greatest flaw in Syracuse urban renewal plans: while the results were certainly uncompromising, the decisions—and decision-makers—were capricious if not downright capitulating. Although little protest was raised over the loss of the James Street mansions, newspaper editorial writers nevertheless predicted an “ugly city” essay in Syracuse’s future:

The 1965 Downtown Urban Renewal Plan justly saw its revitalization potential in providing unique opportunities not available in the outlying neighborhoods:

And perhaps the most egregious compromise:

These days, there seems to be the general air that renewal—for real—has arrived downtown, as the old cornerstone buildings that survived are being renovated into high-end condos. Yet while their original beauty is restored, a new ugliness is creeping in:

For as Huxtable wrote, architecture is about far more than aesthetics or silhouettes against the skyline. From her New York Times obituary:

*As posting the article in its entirety might run against Fair Use laws, if you wish to read it, it can be found in the March 15, 1964 edition of New York Times, or the March 28, 1964 edition of the Post-Standard.

[Ada Louise Huxtable] liked Boston’s City Hall when it opened in 1968, although most people didn’t, and she liked it 40 years later, when a young generation of architects was coming around to its Brutalism, but much of the public still wanted to tear it down. The building was “uncompromising,” she wrote.

Like her. ( New York Times, January 8, 2013)

Which brings us to the greatest flaw in Syracuse urban renewal plans: while the results were certainly uncompromising, the decisions—and decision-makers—were capricious if not downright capitulating. Although little protest was raised over the loss of the James Street mansions, newspaper editorial writers nevertheless predicted an “ugly city” essay in Syracuse’s future:

Syracuse has too little that is old and good, so it has suffered a defeat that will hurt it for years in the loss of the great Leavenworth mansion...

Soon it will be a memory and Syracuse will have left only the old and hideous, none of the old and beautiful and no proof, but rather the opposite of it, that it has any respect or reverence for what our fathers accomplished. If we do not cherish and keep our best examples of beauty, we are soon surrounded by the drab and ugly and our lives reflect the environment we have elected. (Post-Standard, July 15, 1950)

The 1965 Downtown Urban Renewal Plan justly saw its revitalization potential in providing unique opportunities not available in the outlying neighborhoods:

Central Syracuse should seek out and encourage those few-of-a-kind supporting activities which, by virtue of their location in or near the central area, contribute to its "optimum" location.and then tore down an entire city block for a new department store, even as the ones that had anchored downtown for decades were closing and moving to the suburban shopping malls.

And perhaps the most egregious compromise:

The mayor is certain that he will be able to stop any thinking along the lines of elevated highways. He said that state officials agreed to “review the situation.” Mayor Henninger added he has learned that such elevated highways “have ruined other cities.” The mayor also pointed out that he and his administration would “have to move fast. We are on top of this and will keep after it.” (Post-Standard, April 13, 1958)

Syracuse Mayor Anthony A. Henninger indicated the city will not hold out for a depressed-type construction. He is more interested in getting the highway built than quibbling over whether it will be built above or below ground level, he indicated. (Post-Standard, February 25, 1960)

These days, there seems to be the general air that renewal—for real—has arrived downtown, as the old cornerstone buildings that survived are being renovated into high-end condos. Yet while their original beauty is restored, a new ugliness is creeping in:

“It’ll be a different corner,” said David Nutting, the chairman and CEO of VIP Structures, whose bid for a $25 million redevelopment of four buildings across from the Dunkin’ Donuts stipulated the long-planned bus move must happen for the Pike Block project to go forward.

Would Nutting have taken on the project – with its 78 apartments, 25,000-square-feet of retail space and new walkway to the more bustling Armory Square – if the buses and riders had stayed?

“I don’t think so,” he said.

For as Huxtable wrote, architecture is about far more than aesthetics or silhouettes against the skyline. From her New York Times obituary:

Though knowledgeable about architectural styles, Ms. Huxtable often seemed more interested in social substance. She invited readers to consider a building not as an assembly of pilasters and entablatures but as a public statement whose form and placement had real consequences for its neighbors as well as its occupants.

“I wish people would stop asking me what my favorite buildings are,” Ms. Huxtable wrote in The Times in 1971, adding, “I do not think it really matters very much what my personal favorites are, except as they illuminate principles of design and execution useful and essential to the collective spirit that we call society.

“For irreplaceable examples of that spirit I will do real battle.”

*As posting the article in its entirety might run against Fair Use laws, if you wish to read it, it can be found in the March 15, 1964 edition of New York Times, or the March 28, 1964 edition of the Post-Standard.