As well reported and celebrated, twenty years ago, on October 15, 1990, Carousel Center opened its doors and changed the shopping landscape of Syracuse forever. Not surprising, another landscape-altering mall's October 15 birthday passed with no fanfare, much like it has for the past 23 years.

Monday, October 18, 2010

Sunday, September 12, 2010

August 30, 2010

(Continued from Part 1)

In the late 1940s, the Parking Authority made small gains in their parking mission. In 1949, municipal parking lots opened on the northern and southern edges of downtown, at the corner of Oswego Boulevard and North Salina Street and Oneida and West Adams Streets. Each lot offered approximately 200 spaces. But as the Post-Standard had predicted several years earlier, the number of cars on the streets of Syracuse was increasing exponentially. Furthermore, building materials were no longer in short supply as they had been in the years immediately following WWII, resulting in a burst of suburban home and business construction. Yet despite this rapid growth, the Parking Authority's 1950 proposed parking site was decidedly retro:

Despite being shot down for a similar proposal two years earlier, the Parking Authority resurrected their wish to use Clinton Square for parking, though this time around they added Forman Park to the mix as well. According to a June 21, 1950 Post-Standard article, the authority had "abandoned all thoughts suggested last year of double- and triple-decker parking facilities preferring to use street level accommodations solely." In other words, perhaps in an effort to mimic the suburban parking lots, the parking authority sought open land where there was none. As the Post-Standard realized, "Fayette and Columbus parks and other similar spots of green in the community appear in danger of elimination to serve as space for cars."

Granted, Syracusans may have loved their cars, but they didn't want "the sight of 62 cars, even though all are of the latest model" taking over the downtown parks (from letter to the editor, Post-Standard, June 20, 1950). Residents took up their pens in protest:

Letters appeared daily on the editorial pages, as well as editorials from both the Post-Standard and Herald-Journal condemning the decision. Initially, even in the face of this opposition, Mayor Thomas Corcoran "sided with the authority, declaring parking space is more necessary than beauty, especially when it will produce revenue from parking meters." (Post-Standard, June 22, 1950). But exactly one week after the triumphant headlines, the Sunday paper carried far different news:

The following week, the paper once again confirmed the news, stating that "the Parking Authority will meet Thursday to reject the proposal for converting Clinton Square and Forman Park into municipal parking lots" (Syracuse Herald-American, July 2, 1950). When you consider this swift reconsideration by the city after the overwhelming protest by Syracuse residents, you can't help but wonder if the razing of buildings that occurred during the urban renewal years would have had a different outcome had there been similar unified outrage. Unfortunately, the answer can be found within the same letters and editorials:

***

By 1953, the downtown parking situation had become so dire that a 15-part (yes, fifteen part) series about the problem was published in the Post-Standard. In Part 1, reporter Luther Bliven summarized the problem quite succinctly:

Unfortuntately for Mr. Bliven and the Post-Standard, the next 14 articles in the series weren't devoted to reimagining downtown as an alternative to the suburbs, but rather, the hopeless cause of trying to compete with suburban parking. Certainly, Bliven engaged in an extensive amount of research:

Bliven's final recommendation? "Private individuals—investors, bankers or real estate men—should promote construction of one or two ramp garages to accommodate 800 cars." (Post-Standard, May 3, 1953) 15 articles and countless hours of interviews and research, and Bliven thought the problem could be solved with an 800-car garage? Six months earlier, an A&P had opened at the new Valley Plaza, highlighting its 800-car parking lot:

Suburban supermarkets and shopping centers routinely advertised the availability of free parking, almost mocking the downtown situation:

Granted, 800 cars probably never parked at Valley Plaza, and an 800-car garage downtown would have gone a long way to alleviating the parking shortage for shoppers and workers. But drivers weren't relating to numbers, but promises:

800 or 8,000 car garage: the numbers made no difference. Downtown could never guarantee a parking spot steps from the store as the suburbs could. Bliven concluded as much in Part 2:

The knotty problem still remains, as "lack of parking" continues as a reason to avoid downtown to this day, despite the fact that no one has ever seemed to skip a concert or celebrating in Armory Square for lack of a parking spot (except perhaps the 30 O'Brien & Gere employees who had never been downtown, who really need a 15-part series of their own). Yet now as downtown starts to show new signs of life, the parking excuse may start to hold some truth.

Although one of O'Brien & Gere's "downtown orientation sessions" focused on Centro and bike commuting, one would surmise that the majority of the 350 employees of O'Brien & Gere will drive downtown. Winter snow and ice would sideline all but the most experienced bike riders, and Centro—like most city bus systems—limits its riders to schedule and routes. Similarly, one would assume that the majority—if not all—of the condo dwellers downtown also own cars, as the act of buying groceries seems difficult otherwise. As more buildings are converted to condos, and more businesses move downtown, how will this be sustainable? With no convenient alternative means of transportation to and from downtown, how is this any different than sixty years ago?

The recent Post-Standard article about the new O'Brien & Gere downtown office offers walkability as a motive for relocation:

What is unclear, however, is where this walkability begins and ends. Should Downtown merely be a driving destination that is walkable? Or should it be more reflective of its heyday, when downtown was the crossroads of a city connected by streetcar lines? While there seems to be great excitement into turning Downtown into a full-fledged neighborhood (complete with proposed grocery store in the old Dey's building), how would a Downtown dweller travel to any other neighborhood in the Syracuse area without his/her car? Should the "50 to 70 [O'Brien & Gere] visitors a day — customers and out-of-town employees" be required to rent cars or take taxis? And in these respects, how would a revived downtown be any different than a thriving suburb?

***

In the years immediately following WWII, Syracuse couldn't consider city planning without cars as the central focus, as doing so would be a step away from a culture fixated on the future. Technology had won the war; how could it not solve a simple problem like parking? Thus the Strand Theater demolition for a mechanical parking garage, never giving thought to the simple problem that if everyone left an event at the same time, waiting for your car to arrive via elevator might be inconvenient. When the elevated portion of the "modern expressway" finally materialized, city leaders seemed more enamored with the availability of parking underneath. And in the throwback to the war years, when factories were converted for use towards the war effort, a 1974 proposal to build a new library to house a parking garage:

The math has never worked on downtown parking because cars were never meant to be part of the downtown equation. Downtowns have tried to adapt, with parking garages and lots, but what results is a confused hybrid of suburban shopping center and downtown, or more appropriately, a city that can't pinpoint its soul. After suffering from this stigma for decades, downtown is now considered "poised" for a comeback. But for all the new development, if the answer to this one old piece of business isn't thoroughly discussed, that little park at Fayette and West street might become "a gathering point" for a revitalized city center...as downtown's newest parking lot.

"Some years ago the center of the city, namely Clinton Square, was devoted to the parking of cars and the appearance of the city at that place where it should look best to the person driving through was a mess. Now after creating a thing of beauty there to eliminate that horrible mess, our elected officials again want to mess up that spot just to park a measly 60 cars. How thrilling! Just think, all of sixty cars; not a drop in the bucket. It shows a great deal of advancement. Actually, it shows the thinking of small children." (excerpt from a letter to the editor written by Merritt G. Curtis, Syracuse, Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 20, 1950)

In the late 1940s, the Parking Authority made small gains in their parking mission. In 1949, municipal parking lots opened on the northern and southern edges of downtown, at the corner of Oswego Boulevard and North Salina Street and Oneida and West Adams Streets. Each lot offered approximately 200 spaces. But as the Post-Standard had predicted several years earlier, the number of cars on the streets of Syracuse was increasing exponentially. Furthermore, building materials were no longer in short supply as they had been in the years immediately following WWII, resulting in a burst of suburban home and business construction. Yet despite this rapid growth, the Parking Authority's 1950 proposed parking site was decidedly retro:

Despite being shot down for a similar proposal two years earlier, the Parking Authority resurrected their wish to use Clinton Square for parking, though this time around they added Forman Park to the mix as well. According to a June 21, 1950 Post-Standard article, the authority had "abandoned all thoughts suggested last year of double- and triple-decker parking facilities preferring to use street level accommodations solely." In other words, perhaps in an effort to mimic the suburban parking lots, the parking authority sought open land where there was none. As the Post-Standard realized, "Fayette and Columbus parks and other similar spots of green in the community appear in danger of elimination to serve as space for cars."

Granted, Syracusans may have loved their cars, but they didn't want "the sight of 62 cars, even though all are of the latest model" taking over the downtown parks (from letter to the editor, Post-Standard, June 20, 1950). Residents took up their pens in protest:

To the Herald Journal:

A characteristic nibble at the edge of a big problem is the plan to turn Clinton Square into a parking lot. Syracuse is still trying to run a big city on a country village level.

The Square, which is not only a welcome spot of beauty in a rushing downtown section, but is supposed to have some memorial significance, will park a few cars, true. But it will certainly not improve the beauty of our city, which the planners praise about, when it is turned into a car lot.

Syracuse is still living down the reputation as the town where "the trains run through the streets." Now it can build up another as the city which uses its Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Square for a parking lot. (from a letter signed Cross-Town Pedestrian, June 20, 1950)

To the editor of the Post-Standard:

The following is a letter I have sent to Mayor Corcoran:

As a descendant of two of the pioneers of Syracuse, I wish to add my protest to the many others you have received, against the destroying of two of the few remaining beauty spots now left in downtown Syracuse: namely, the fountain in Clinton Square and Forman Park, established in honor of another of the founders of our city.

My ancestor, Oliver Teall, was one of the engineers instrumental in building the Erie Canal through this area.

My father, Timothy H. Teall, exhibited the first electric light in Syracuse.

It will take a lot of parking revenue to reimburse the taxpayers for the cost of the Clinton Square fountain, as was reported in this week's paper. Then, too, we will not have a little place for our municipal Christmas tree, which is one of the pleasant items in a cold winter. Don't sacrifice everything for a little more money.

Also, have you the legal right to destroy our property?

(from a letter signed H.L. Teall, Post-Standard, June 27, 1950 - also printed in Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 28, 1950)

Letters appeared daily on the editorial pages, as well as editorials from both the Post-Standard and Herald-Journal condemning the decision. Initially, even in the face of this opposition, Mayor Thomas Corcoran "sided with the authority, declaring parking space is more necessary than beauty, especially when it will produce revenue from parking meters." (Post-Standard, June 22, 1950). But exactly one week after the triumphant headlines, the Sunday paper carried far different news:

|

| From Syracuse Herald-American, June 25, 1950 |

The city has broached the idea of turning Forman Park and part of Clinton Square into parking areas.

It is simply an admission of defeat.

There are plenty of ramshackle old buildings that could be torn down in congested areas and the sites turned into parking spaces, without turning to the few bits of nature that Syracuse owns. (from Post-Standard editorial, June 20, 1950)

To the editor of the Post-Standard:

I wish to protest against the plans of the city to use part of Clinton Square and Forman Park for parking lots. Why couldn't some of the old unsightly buildings in the downtown area be condemned and torn down and the land used for parking areas, thereby improving the community. (from letter signed J.B., Post-Standard, June 25, 1950)

To the Herald-Journal:

Why don't we tear down some of the ramshackle old buildings around town and build a real building for parking of cars instead of making an ugly blot out of that little beauty spot and putting us back in the horse and buggy era. (from a letter signed Isha, Herald-Journal, June 24, 1950)

***

By 1953, the downtown parking situation had become so dire that a 15-part (yes, fifteen part) series about the problem was published in the Post-Standard. In Part 1, reporter Luther Bliven summarized the problem quite succinctly:

The average driver is an eternal optimist, certain that if he keeps circling long enough he will find a parking space reasonably near where he wants to go. If parking is completely prohibited in the area of his destination, he may have a passenger go in and do his errand. Meanwhile he circles the block until the errand is completed. Both maneuvers produce more traffic congestion.

...

Unless the people can enter and leave the central business district without being unduly delayed by traffic congestion, and can find a place to park reasonably near their destination, they will purchase merchandise and commercial and professional services elsewhere, usually in suburban shopping centers. (Post-Standard, April 19, 1953)

Unfortuntately for Mr. Bliven and the Post-Standard, the next 14 articles in the series weren't devoted to reimagining downtown as an alternative to the suburbs, but rather, the hopeless cause of trying to compete with suburban parking. Certainly, Bliven engaged in an extensive amount of research:

During his preparation of the series, Mr. Bliven compared the Syracuse situation with that of 15 other cities from coast to coast; analyzed reports on the problem prepared by Syracuse and other cities; held personal interviews with more than 30 Syracusans closely acquainted with the parking and traffic needs of the city.

He also consulted at length with two nationally-recognized authorities on the subject; interviewed 23 persons in Allentown and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; corresponded with municipal, chamber of commerce and merchants' parking group authorities in 12 other cities; studied articles dealing with the subject in such magazines as Architectural Forum, Life, Collier's and other publications; conferred with many persons who have called in with suggestions since the series started. (Post-Standard, May 3, 1953)

Bliven's final recommendation? "Private individuals—investors, bankers or real estate men—should promote construction of one or two ramp garages to accommodate 800 cars." (Post-Standard, May 3, 1953) 15 articles and countless hours of interviews and research, and Bliven thought the problem could be solved with an 800-car garage? Six months earlier, an A&P had opened at the new Valley Plaza, highlighting its 800-car parking lot:

|

| Post-Standard, December 3, 1952 |

Suburban supermarkets and shopping centers routinely advertised the availability of free parking, almost mocking the downtown situation:

|

| from A&P ad, Post-Standard, December 3, 1952 |

Granted, 800 cars probably never parked at Valley Plaza, and an 800-car garage downtown would have gone a long way to alleviating the parking shortage for shoppers and workers. But drivers weren't relating to numbers, but promises:

|

| Syracuse Herald-Journal, February 14, 1951 |

800 or 8,000 car garage: the numbers made no difference. Downtown could never guarantee a parking spot steps from the store as the suburbs could. Bliven concluded as much in Part 2:

The city's parking shortage and traffic congestion problems are compounded by the fact that 70 percent of more than 30,000 drivers who enter the main business area daily insist on parking at the curb where only about one-seventh of the total downtown parking space is available.

Many who would gloss over the knotty problem maintain, "the parker must learn to walk a few blocks farther." Extensive studies in Syracuse, and many other cities, show he is not inclined." (Post-Standard, April 20, 1953)

The knotty problem still remains, as "lack of parking" continues as a reason to avoid downtown to this day, despite the fact that no one has ever seemed to skip a concert or celebrating in Armory Square for lack of a parking spot (except perhaps the 30 O'Brien & Gere employees who had never been downtown, who really need a 15-part series of their own). Yet now as downtown starts to show new signs of life, the parking excuse may start to hold some truth.

Although one of O'Brien & Gere's "downtown orientation sessions" focused on Centro and bike commuting, one would surmise that the majority of the 350 employees of O'Brien & Gere will drive downtown. Winter snow and ice would sideline all but the most experienced bike riders, and Centro—like most city bus systems—limits its riders to schedule and routes. Similarly, one would assume that the majority—if not all—of the condo dwellers downtown also own cars, as the act of buying groceries seems difficult otherwise. As more buildings are converted to condos, and more businesses move downtown, how will this be sustainable? With no convenient alternative means of transportation to and from downtown, how is this any different than sixty years ago?

The recent Post-Standard article about the new O'Brien & Gere downtown office offers walkability as a motive for relocation:

A new generation of employees wants something else, said Dot Hall, a senior manager. Surveying college graduates who declined O’Brien & Gere job offers, Hall learned they wanted to work in cities where they can walk to restaurants, shops and entertainment.

What is unclear, however, is where this walkability begins and ends. Should Downtown merely be a driving destination that is walkable? Or should it be more reflective of its heyday, when downtown was the crossroads of a city connected by streetcar lines? While there seems to be great excitement into turning Downtown into a full-fledged neighborhood (complete with proposed grocery store in the old Dey's building), how would a Downtown dweller travel to any other neighborhood in the Syracuse area without his/her car? Should the "50 to 70 [O'Brien & Gere] visitors a day — customers and out-of-town employees" be required to rent cars or take taxis? And in these respects, how would a revived downtown be any different than a thriving suburb?

***

In the years immediately following WWII, Syracuse couldn't consider city planning without cars as the central focus, as doing so would be a step away from a culture fixated on the future. Technology had won the war; how could it not solve a simple problem like parking? Thus the Strand Theater demolition for a mechanical parking garage, never giving thought to the simple problem that if everyone left an event at the same time, waiting for your car to arrive via elevator might be inconvenient. When the elevated portion of the "modern expressway" finally materialized, city leaders seemed more enamored with the availability of parking underneath. And in the throwback to the war years, when factories were converted for use towards the war effort, a 1974 proposal to build a new library to house a parking garage:

The math has never worked on downtown parking because cars were never meant to be part of the downtown equation. Downtowns have tried to adapt, with parking garages and lots, but what results is a confused hybrid of suburban shopping center and downtown, or more appropriately, a city that can't pinpoint its soul. After suffering from this stigma for decades, downtown is now considered "poised" for a comeback. But for all the new development, if the answer to this one old piece of business isn't thoroughly discussed, that little park at Fayette and West street might become "a gathering point" for a revitalized city center...as downtown's newest parking lot.

Monday, August 23, 2010

August 14, 1945

"You've lost. You just don't know it."

"I've lost? Look at the board."

"I have."

—scene from the film Searching for Bobby Fischer

On August 14, 1945, upon the news of Japan's surrender in World War II, "crowds of persons streamed downtown as if pushed by an avalanche":

Downtown Syracuse was the centerpiece of a celebration, not only of the end of the war but of the prosperity to follow: one year earlier, General Electric announced the construction of Electronics Park, the main manufacturing center of the General Electric electronics department. The 10 million dollar project covering 155 acres and 1 million square feet of floor space was so massive that "nothing in Syracuse [could] touch it for size and modernity." (Syracuse Herald-American, September 23, 1945). On June 23, 1945, a Syracuse Herald-Journal editorial addressed the "bright days ahead for our city":

Yet on the very same page, one column to the right, another Herald-Journal editorial glimpsed a possible shadow on this glowing future:

They most certainly would be unique among American cities, as they would be achieving the impossible: fitting thousands of cars within steps-only walking distance of every downtown shop, while still trying to maintain the existence of downtown. By the mid-1940s, editorial writers realized that that even the high-tech innovations of Electronics Park couldn't solve the low-tech issue of downtown parking:

They also glimpsed what the success and growth of post-WWII Syracuse could mean for downtown:

In the years and decades ahead, downtown would experience that loss: loss of business, loss of buildings, loss of the very institutions—the grand movie palaces and theaters—that could have offered the city center a competitive edge over the suburbs. Indeed, when we think of what could have been, it's easy to imagine touring Broadway shows at RKO Keith's or the Strand Theater, drawing Wicked-sized crowds to Downtown on a monthly basis. But just think: there may also have been no Connective Corridor or Clinton Square fountain use to debate; no Urban Outfitters or O'Brien & Gere grand openings to gush over. Not because downtown would have been such a glittering jewel that we wouldn't need year-long orientation sessions for its newest employees, but rather, had certain Syracuse citizens not been victorious in their own personal battles for downtown, Forman Park, Clinton Square and Armory Square today would be supersized parking lots.

***

In 1947, Mayor Frank Costello named a five-member commission (Charles Chappell, Henry Menopace, president of the Syracuse Real Estate Board, Frederick Norton, secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, Jerome Rusterholtz, automobile dealer, and G. Frank Wallace, businessman and former state senator) to solve the city's parking problem. The announcement of the new authority came in conjunction with the release of a report of an off-street parking program prepared by the City Planning Commission, which made several suggestions for permanent parking facilities:

View 1947 Parking Solutions in a larger map

Although subterranean parking lots were then being constructed in other cities, the report declared the proposal of building garages under streets or parks downtown "impractical." Yet, really, none of the suggestions in the report could be considered practical, as the city had neither means nor method for advancing this plan. After a year of much talk and no action, perhaps the Syracuse Herald-American could be forgiven for not believing the Authority's announcement of a new potential solution as particularly newsworthy:

Clinton Square had once before been used solely for parking, in the years immediately following the paving-over of the Erie Canal. In 1933, the city embarked upon the "beautification of Clinton Square," based on plans submitted by architect Dwight Baum:

Perhaps it is easier to understand how the Strand Theater and similar historic landmarks could be sacrificed in the 1950s when you read that a mere decade after this landscaping makeover, Clinton Square was offered up for an 62-car parking lot. Sensing a battle, neighborhood garden clubs immediately voiced their disapproval:

The Syracuse Society of Architects protested the proposal, declaring the scheme "inadequate and would only serve to increase the traffic problem downtown and destroy one of the most prominent aesthetic areas of the city." (Post-Standard, January 30, 1948) Even a Post-Standard editorial decried the plan:

Within six months, the Parking Authority seemed to lose interest in Clinton Square, as they had arrived at at new possibility: razing a full city block to build a giant parking garage:

While the Jefferson-Clinton Hotel would be spared, other buildings—occupied with tenants—would be condemned and demolished for the structure, which offered the promise of being one block away South Salina Street:

On July 8, the Syracuse Parking Authority stated that in "about two weeks" they would take "concrete action to acquire the property and demolish buildings." (Post-Standard, July 8, 1948). One week later, the property formerly housing the St. Vincent Orphanage at Madison and Montgomery Streets, was offered to the city for purchase for a parking lot. Thus ended the plan to bulldoze this particular block, though once again the news was buried on the inside pages:

But when the Parking Authority announced their next proposed site, the plan sounded so audacious—or inept—that headlines would be splashed across the front page of the Sunday paper.

Coming soon: Part 2

The Post-WWII Emerald City: Razing parks but recycling ideas!

"I've lost? Look at the board."

"I have."

—scene from the film Searching for Bobby Fischer

On August 14, 1945, upon the news of Japan's surrender in World War II, "crowds of persons streamed downtown as if pushed by an avalanche":

|

| Post-Standard, August 15, 1945 |

Downtown Syracuse was the centerpiece of a celebration, not only of the end of the war but of the prosperity to follow: one year earlier, General Electric announced the construction of Electronics Park, the main manufacturing center of the General Electric electronics department. The 10 million dollar project covering 155 acres and 1 million square feet of floor space was so massive that "nothing in Syracuse [could] touch it for size and modernity." (Syracuse Herald-American, September 23, 1945). On June 23, 1945, a Syracuse Herald-Journal editorial addressed the "bright days ahead for our city":

Remarks of District Manager Mason of the War Production Board in his address before the Advertising Club are profoundly encouraging from the standpoint of all citizens interested in postwar prosperity for Syracuse.

...

Not only are some of our largest industries planning broad expansion but new industries promise beneficent results from the standpoint of the community as a whole. For example, the General Electric Electronics Park development, which promises to become the world center of the electronics industry, will mean employment for thousands in postwar years.

These are bright days ahead for Syracuse.

Yet on the very same page, one column to the right, another Herald-Journal editorial glimpsed a possible shadow on this glowing future:

In planning for the postwar progress and prosperity of Syracuse, thoughtful consideration must be given to the problem of providing more adequate parking facilities in or near the business heart of the city.

...

The parking situation undoubtedly will grow progressively worse as more gasoline becomes available and new cars come into the market.

In its report covering the Central District of Syracuse, the Syracuse-Onondaga Postwar Planning Council remarked that "assurance of ample parking facilities is a matter of public responsibility. It does not make sense to provide public highways and streets for moving vehicles and make no provision for them at rest..."

...

We are aware, of course, that the parking problem is present in exaggerated form in practically every American city. Syracuse is not unique in that respect: it is in the same class as the majority of American municipalities.

But if we could solve this problem, it would be a momentous development from the standpoint of the city's future. Then we would be unique among American cities.

They most certainly would be unique among American cities, as they would be achieving the impossible: fitting thousands of cars within steps-only walking distance of every downtown shop, while still trying to maintain the existence of downtown. By the mid-1940s, editorial writers realized that that even the high-tech innovations of Electronics Park couldn't solve the low-tech issue of downtown parking:

There is not much use in trying to find more parking space at curbs in the business section of the city. There are five cars now for every space (at 45-minute intervals) and before long there will be 10 of them.

They also glimpsed what the success and growth of post-WWII Syracuse could mean for downtown:

The traffic laws are badly misused. But we should realize, too, that it is largely a result of desperation. There are many more cars than there are parking spaces.

If we do not solve the problem, we'll have stores scattering to different parts of the city. We'll lose heavily. (Post-Standard editorial, February 20, 1946)

In the years and decades ahead, downtown would experience that loss: loss of business, loss of buildings, loss of the very institutions—the grand movie palaces and theaters—that could have offered the city center a competitive edge over the suburbs. Indeed, when we think of what could have been, it's easy to imagine touring Broadway shows at RKO Keith's or the Strand Theater, drawing Wicked-sized crowds to Downtown on a monthly basis. But just think: there may also have been no Connective Corridor or Clinton Square fountain use to debate; no Urban Outfitters or O'Brien & Gere grand openings to gush over. Not because downtown would have been such a glittering jewel that we wouldn't need year-long orientation sessions for its newest employees, but rather, had certain Syracuse citizens not been victorious in their own personal battles for downtown, Forman Park, Clinton Square and Armory Square today would be supersized parking lots.

***

On nearly every street in the business section of Syracuse there are vacant lots once occupied by business blocks that are now torn down. These are mostly used as parking lots.

...

All over the city the same condition prevails. At the rate business buildings are being torn down, it will not be long before the entire downtown district will be one vast parking lot. (from a letter to the editor, Syracuse Herald-Journal, May 5, 1944)

In 1947, Mayor Frank Costello named a five-member commission (Charles Chappell, Henry Menopace, president of the Syracuse Real Estate Board, Frederick Norton, secretary of the Chamber of Commerce, Jerome Rusterholtz, automobile dealer, and G. Frank Wallace, businessman and former state senator) to solve the city's parking problem. The announcement of the new authority came in conjunction with the release of a report of an off-street parking program prepared by the City Planning Commission, which made several suggestions for permanent parking facilities:

View 1947 Parking Solutions in a larger map

Although subterranean parking lots were then being constructed in other cities, the report declared the proposal of building garages under streets or parks downtown "impractical." Yet, really, none of the suggestions in the report could be considered practical, as the city had neither means nor method for advancing this plan. After a year of much talk and no action, perhaps the Syracuse Herald-American could be forgiven for not believing the Authority's announcement of a new potential solution as particularly newsworthy:

|

| "Parking may replace park." January 18, 1948 |

Clinton Square had once before been used solely for parking, in the years immediately following the paving-over of the Erie Canal. In 1933, the city embarked upon the "beautification of Clinton Square," based on plans submitted by architect Dwight Baum:

Perhaps it is easier to understand how the Strand Theater and similar historic landmarks could be sacrificed in the 1950s when you read that a mere decade after this landscaping makeover, Clinton Square was offered up for an 62-car parking lot. Sensing a battle, neighborhood garden clubs immediately voiced their disapproval:

To the Editor of the Post-Standard:

Enclosed is a letter sent to Mayor Costello.

Alan F. Burgess (President, Garden Center Association)

Recently some publicity has been given to a proposal to convert the southern half of Clinton Square to a parking lot, as a partial solution to the need for off-the-street parking.

I wish to inform you that at its regular monthly meeting today, the Garden Center Association, which represents 27 Garden Clubs in Syracuse and Central New York, voted unanimously to go on record as opposing this proposal, and to inform you of its action.

While we realize the need for increased parking space in downtown Syracuse, we believe that the proposed change in Clinton Square would actually provide space for a mere handful of cars, while detracting considerably from the appearance of this park, in the heart of our city.

There are already too many unattractive areas in Syracuse, without creating one more where thousands of tourists pass through annually.

(Post-Standard, January 25, 1948)

The Syracuse Society of Architects protested the proposal, declaring the scheme "inadequate and would only serve to increase the traffic problem downtown and destroy one of the most prominent aesthetic areas of the city." (Post-Standard, January 30, 1948) Even a Post-Standard editorial decried the plan:

The garden clubs of Syracuse are right in fighting a proposal to give Clinton Square over to off-street parking.

We can't afford to give away any beauty.

Such a proposal is an admission of defeat. There are, or ought to be, plenty of other places to park cars. It is a question of going ahead and doing the thing right. (Post-Standard, January 22, 1948)

Within six months, the Parking Authority seemed to lose interest in Clinton Square, as they had arrived at at new possibility: razing a full city block to build a giant parking garage:

The new Syracuse Parking Authority is seriously considering purchase of the block bounded by S. Clinton, S. Franklin, Walton and W. Jefferson Streets as a parking lot.

The authority met yesterday afternoon and afterward (authority chairman) G. Frank Wallace said that if this plan proves successful a building of several stories to provide parking may be erected on the lot. The proposal would involve razing all buildings in the block excepting the Jefferson-Clinton Hotel. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 19, 1948).

|

| Post-Standard, June 21, 1948 |

While the Jefferson-Clinton Hotel would be spared, other buildings—occupied with tenants—would be condemned and demolished for the structure, which offered the promise of being one block away South Salina Street:

The proposal was termed "ridiculous" by Charles H. Kaletzki, Syracuse advertising man and owner of the Bohanon Company, an occupant of Wood's building.

Kaletzki said the frontage was valuable and questioned the advisability of ripping out a revenue-producing building for the comparatively small revenue that would be produced by a parking lot. (Post-Standard, June 21, 1948)

On July 8, the Syracuse Parking Authority stated that in "about two weeks" they would take "concrete action to acquire the property and demolish buildings." (Post-Standard, July 8, 1948). One week later, the property formerly housing the St. Vincent Orphanage at Madison and Montgomery Streets, was offered to the city for purchase for a parking lot. Thus ended the plan to bulldoze this particular block, though once again the news was buried on the inside pages:

But when the Parking Authority announced their next proposed site, the plan sounded so audacious—or inept—that headlines would be splashed across the front page of the Sunday paper.

Coming soon: Part 2

The Post-WWII Emerald City: Razing parks but recycling ideas!

Sunday, July 25, 2010

July 7, 1940

Yes, the blog has been on a bit of a summer break. I haven't taken any major summer vacations myself, although earlier this month I did travel to Syracuse for a weekend for the 75th Anniversary Celebration of my alma mater school district. While I always anticipate a visit to Wegmans on a return trip home, it seems Syracuse is currently enamored with the business just across the Fairmount Wegmans parking lot: Five Guys.

I am not in the Five Guys target market (neither having lived in Syracuse nor eaten a hamburger for almost two decades), but I nevertheless read the Store Front blog extensive coverage of Five Guys recent opening with great fascination. Even more astonishing were the pictures of Black Friday-length lines for the opening of Cici's Pizza in DeWitt. Although some of the fastest-growing franchises choosing Syracuse suggests confidence in the area as a consumer market, what does it mean when the area's landscape is chained to establishments that can be found in any city in the country?

Certainly, a Faimount-based Five Guys is convenient if you live in the area and have a hunger for a 920-calorie bacon cheeseburger. But celebrating—even championing—the arrival of a chain restaurant operating 250 locations in 19 states also seems somewhat reminiscent of the Herald-Journal’s 1940 search for Syracuse’s most typical family:

Ninety-five families wrote letters to the paper in this competition of commonplace. A panel of five judges, including T. Aaron Levy, Reverends Walter D. Cavert and J. James Bannon, Welfare Department Commissioner Leon Abbott and Syracuse University professor Dr. Frances Markey Dwyer, sought to find the most ordinary, conventional family to represent Syracuse in a national competition of "the All-American Family," to be held at the 1939-40 World’s Fair in New York:

Thirty-one families were chosen via similar newspaper contests around the country, and all winners were treated to a prize vacation:

Being as families have humiliated themselves on reality shows in recent years and not won prizes this substantial, one can only imagine how valuable this opportunity sounded to Central New York families at the end of the Depression. So the Cramer family of 302 Dewitt Road strove to sound as simple as can be:

Not unlike, say, chain restaurants.

***

While home in Syracuse, I saw a commercial for the Creative Core air repeatedly on local stations. After each viewing, I found myself more confused as to the point of the ad. Initially I thought the ad was promoting tourism and/or relocation, but if so, why the repeat local airings? Or is it solely a local ad, presenting a new outlook/brand for the region to those who already live there?

Perhaps my confusion is the same when I read the store front blog with its frequent excitement for chain restaurants locating in the Syracuse area. Is this enthusiasm simply about eliminating a road trip to get that chain's signature meal? Or is there the hope that tourists and new residents will now flock to Syracuse? And if they do, what will they see when they arrive? In the week prior to my visit to Syracuse, I took day trips to Foxborough, Massachusetts and New York City, where I also spotted Five Guys locations. Walk out of Five Guys on Bleecker Street and find yourself in the West Village; Five Guys in Patriot Place is steps away from Gillette Stadium. Exit the Creative Core Five Guys and enjoy...the equally-celebrated chain Panera Bread?

But where else would Five Guys be in the Syracuse area? Not downtown, with Five Guys real estate requirements of "minimum 35 dedicated parking spaces (if not a high pedestrian area)" and avoidance of co-tenants such as "low-volume retail and businesses that close on the evenings and weekends." Olive Garden? 7,500 – 8,500 building square footage, 1.7-2.4 acres of land, and 125-145 parking spaces. Longhorn Steakhouse and Bahama Breeze, two restaurants on syracuse.com commenters' wishlist to replace the vacant Hooters space at Carousel Center? 5550 building square footage, 1.38+ acres, 116+ parking spaces and 7000 building square footage, 1.9 acres and 140-160 parking spaces, respectively. And Panera Bread?

• 3,500– 4,500 square feet of mostly rectangular vanilla box

space plus patio area for 35 + seats

• Proximity to morning, afternoon and evening traffic generators

• Prefer high visibility in-line or end cap locations in shopping centers or malls, free standing or pad site locations

• Traffic count of 20,000 cars per day

• 10,000 people within one mile ring

• 30,000 people within two mile ring

• 40 feet of visible store frontage

• 50,000 people within three mile ring

• One parking space per 3 chairs, a minimum of 70 spaces

• Minimum of 110 seats

• 70% of population within one and two mile rings within the top 1/3 Prizm clusters

• Ten year primary term with three five year options

• Convenient ingress and egress

• Business employment count of 10,000 within one-mile ring and 20,000 within two mile ring

• Visibility from all directions

• Median household income of $ 50,000

Celebrating the arrival of more chain restaurants in the Syracuse region may confirm that the area has the population and median income requirements—a worthy distinction—but also perpetuates the pattern of suburban growth presented at the World's Fair seven decades ago.

When this future(ama) came to pass, city centers (in Syracuse and elsewhere) attempted to recreate themselves in the pattern of suburbs. Now, as Downtown Syracuse continues its revitalization efforts from this mistake, it too has seen a recent spate of restaurant openings. However, in a step away from suburban development, the new downtown restaurants are independently owned. These establishments, as well as the many other non-chain restaurants in Syracuse and surrounding areas, are the unique institutions that must come to typically define Syracuse.

Just some locally-grown food for thought.

I am not in the Five Guys target market (neither having lived in Syracuse nor eaten a hamburger for almost two decades), but I nevertheless read the Store Front blog extensive coverage of Five Guys recent opening with great fascination. Even more astonishing were the pictures of Black Friday-length lines for the opening of Cici's Pizza in DeWitt. Although some of the fastest-growing franchises choosing Syracuse suggests confidence in the area as a consumer market, what does it mean when the area's landscape is chained to establishments that can be found in any city in the country?

Certainly, a Faimount-based Five Guys is convenient if you live in the area and have a hunger for a 920-calorie bacon cheeseburger. But celebrating—even championing—the arrival of a chain restaurant operating 250 locations in 19 states also seems somewhat reminiscent of the Herald-Journal’s 1940 search for Syracuse’s most typical family:

Will you help us find the most typical family in Central New York?

Maybe it is yours?

At any rate once this family is discovered, the father, mother and two children will be treated to the finest vacation you could possibly imagine—and the entire trip will not cost them one penny.

The opportunity for entrance in this unique contest will be over at midnight next Saturday so if you have a family that you think is average in this section of the state, enter it today! (Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 22, 1940).

Ninety-five families wrote letters to the paper in this competition of commonplace. A panel of five judges, including T. Aaron Levy, Reverends Walter D. Cavert and J. James Bannon, Welfare Department Commissioner Leon Abbott and Syracuse University professor Dr. Frances Markey Dwyer, sought to find the most ordinary, conventional family to represent Syracuse in a national competition of "the All-American Family," to be held at the 1939-40 World’s Fair in New York:

No one knows exactly what an average Central New York family should be. That will be the duty of the committee to decide. But if a family far from average in one or two respects and near average in all their other qualifications, the sum total of all their qualities would approximate the normal living standard of this section of the State and they might be chosen as the winning family.

Don't forget that the family that comes closest to what the judges believe is normal for this section of the State will be awarded the free trip to the fair. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 26, 1940)

Thirty-one families were chosen via similar newspaper contests around the country, and all winners were treated to a prize vacation:

As soon as the lucky family has been named by the contest committee plans will be made for a glorious week's vacation free at the World's Fair for the typical Central New York family.

A new Ford car and chauffeur will roll up to their doorstep a week from tomorrow and transport them leisurely to New York City and their FHA home residence on the fairgrounds.

The family will be the guests of the Ford Motor Company to and from the fair and will be guests of the exhibition management during their week's stay.

Early next week they will be taken to Sears Roebuck Company where they will be allowed to select $100 worth of clothing for their vacation. Sears Roebuck furnished the model home in which the family will reside at the Fair, and the local retail store will supply the typical family with vacation clothing.

Every penny of expense on the entire trip will be paid so the family will be able to enjoy a grand vacation free from any money worries.

At the Fair the family will be free to choose its own amusements and plan its own itinerary. No stiff luncheons or formal dinners are slated for the typical Central New York family who will enjoy themselves as they would on any private vacation jaunt. (Syracuse Herald-Journal, July 6, 1940)

Being as families have humiliated themselves on reality shows in recent years and not won prizes this substantial, one can only imagine how valuable this opportunity sounded to Central New York families at the end of the Depression. So the Cramer family of 302 Dewitt Road strove to sound as simple as can be:

"A quiet evening at home with the family grouped about the fireplace, the children playing on the floor with their dog, Freckles, Dad reading his favorite magazine, mother sewing, each of us with a dish of popcorn and the radio playing in the background is our idea of the perfect winter evening. We also like to play a family game of Chinese checkers, parcheesi or rummy. Once a week we try to go to a good movie. Sundays, after church and Sunday school, we plan a picnic or an outing in the family car, perhaps to grandma's or the airport, which the children enjoy.Seventy years later, Alice Cramer's words seem to reflect the enduring image of families from that era. While they may have been considered most typical at the time, the winning Cramer family was far from ordinary: Husband Kenneth Cramer co-owned a turkey farm in Baldwinsville, where wife Alice managed the bookkeeping. Kenneth's brother Leonard was a well-known pilot who, in August 1940, traveled to Britain "to train youthful British fliers for the anticipated German blitzkrieg upon England" (Syracuse Herald-Journal, August 7, 1940). Uncle Peter Cramer "passed nine years and six days in [a] trip around the globe traveling principally as a fireman or oiler on freighters...ranched in Australia and the West, been in the crew of fishing vessels off the Russian Arctic coast months at a stretch out of sight of land, seen Hawaii, England, Ireland, Italy, France, Germany, Russia, Mexico and [had] a new home under construction in California having lost his last in a flood" (Syracuse Herald-American, September 15, 1940). But for the World's Fair, conceived in part as an opportunity for corporations to present domestic-related products to a specific audience, individual achievements mattered less than ideal consumers. For fair sponsors, who wished to sell cars and washing machines to a newly emerging middle class, the "typical families" of the United States all looked exactly the same:

As we are buying our home, there isn't much extra money for luxuries and expensive entertainment, so we have built our life around our home and each other and as parents, hope we can always share the confidence and companionship of our children." (excerpt from letter written by Alice Cramer, in Syracuse Herald-American, July 7, 1940)

| |

| Winning West Texas family, from Big Spring Daily Herald, May 13, 1940 |

| ||

| Winning Florida family, from Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 20, 1940 |

|

| The Cramer family, from Syracuse Herald-Journal, July 7, 1940 |

Not unlike, say, chain restaurants.

***

While home in Syracuse, I saw a commercial for the Creative Core air repeatedly on local stations. After each viewing, I found myself more confused as to the point of the ad. Initially I thought the ad was promoting tourism and/or relocation, but if so, why the repeat local airings? Or is it solely a local ad, presenting a new outlook/brand for the region to those who already live there?

Perhaps my confusion is the same when I read the store front blog with its frequent excitement for chain restaurants locating in the Syracuse area. Is this enthusiasm simply about eliminating a road trip to get that chain's signature meal? Or is there the hope that tourists and new residents will now flock to Syracuse? And if they do, what will they see when they arrive? In the week prior to my visit to Syracuse, I took day trips to Foxborough, Massachusetts and New York City, where I also spotted Five Guys locations. Walk out of Five Guys on Bleecker Street and find yourself in the West Village; Five Guys in Patriot Place is steps away from Gillette Stadium. Exit the Creative Core Five Guys and enjoy...the equally-celebrated chain Panera Bread?

But where else would Five Guys be in the Syracuse area? Not downtown, with Five Guys real estate requirements of "minimum 35 dedicated parking spaces (if not a high pedestrian area)" and avoidance of co-tenants such as "low-volume retail and businesses that close on the evenings and weekends." Olive Garden? 7,500 – 8,500 building square footage, 1.7-2.4 acres of land, and 125-145 parking spaces. Longhorn Steakhouse and Bahama Breeze, two restaurants on syracuse.com commenters' wishlist to replace the vacant Hooters space at Carousel Center? 5550 building square footage, 1.38+ acres, 116+ parking spaces and 7000 building square footage, 1.9 acres and 140-160 parking spaces, respectively. And Panera Bread?

• 3,500– 4,500 square feet of mostly rectangular vanilla box

space plus patio area for 35 + seats

• Proximity to morning, afternoon and evening traffic generators

• Prefer high visibility in-line or end cap locations in shopping centers or malls, free standing or pad site locations

• Traffic count of 20,000 cars per day

• 10,000 people within one mile ring

• 30,000 people within two mile ring

• 40 feet of visible store frontage

• 50,000 people within three mile ring

• One parking space per 3 chairs, a minimum of 70 spaces

• Minimum of 110 seats

• 70% of population within one and two mile rings within the top 1/3 Prizm clusters

• Ten year primary term with three five year options

• Convenient ingress and egress

• Business employment count of 10,000 within one-mile ring and 20,000 within two mile ring

• Visibility from all directions

• Median household income of $ 50,000

Celebrating the arrival of more chain restaurants in the Syracuse region may confirm that the area has the population and median income requirements—a worthy distinction—but also perpetuates the pattern of suburban growth presented at the World's Fair seven decades ago.

When this future(ama) came to pass, city centers (in Syracuse and elsewhere) attempted to recreate themselves in the pattern of suburbs. Now, as Downtown Syracuse continues its revitalization efforts from this mistake, it too has seen a recent spate of restaurant openings. However, in a step away from suburban development, the new downtown restaurants are independently owned. These establishments, as well as the many other non-chain restaurants in Syracuse and surrounding areas, are the unique institutions that must come to typically define Syracuse.

Just some locally-grown food for thought.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

May 25, 1974

Continued from Part One

By the 1960s, the city of Syracuse had dismantled much of what had been built in the 1920s: Strand Theater, RKO Keith's, and the May 15, 1923 Syracuse Herald editorial declaration of the "hope that the city has now heard the last proposal from any source for the erection on our park lands of structures that have no place there." (In 1961, city leaders and residents debated building the new Southwest High School (Corcoran) in Onondaga or Kirk Park.) By the 1970s, the city of Syracuse had dismantled much of what had been built in the 1960s: Strand Parking Garage, every memory of the Corcoran/Onondaga Park controversy (in 1971, the Syracuse Board of Education declared Burnet Park an ideal site for Fowler High School), and the Texture Program.

The Texture Program, which suggested focusing on "small-in-themselves" projects for downtown Syracuse, soon became a major component of 1960s city planning. In July 1963, Texture committee members traveled to Ottawa with Mayor Walsh and city council members to view the Sparks Street Mall (Post-Standard, July 28, 1963). At the height of the protests regarding the 15th Ward destruction in October 1963, the Texture Committee tagged along with Mayor Walsh (in a travel party totaling "33 strong") on a "town-planning fact-finding mission to Europe" (Post-Standard, October 11, 1963). It's not quite clear what texture the Texture Committee added to the city during the decade, other than "MDA Texture Committee chairman Winston Rodormer's progress report point[ing] to tree planting and placing of seats in Vanderbilt Square between S. Salina and S. Warren Streets and construction of a courtyard and park of the northeast corner of the Hotel Syracuse" (Post-Standard, December 28, 1963) and hard feelings.

Mentions of the Texture Committee disappeared from newspapers by late 1960s, much like the shoppers in downtown Syracuse itself. After spending a decade in rebuilding mode only to end up in further decline, the city found itself in full-blown panic mode. As their veteran players left to join up the suburban competition, the next quick-fix plan seemed obvious:

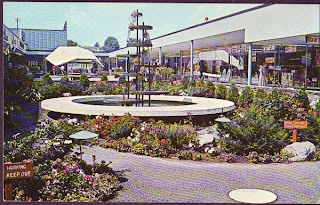

The mall Mayor Henninger proposed in the 1950s sounds very much like a replica of the then-brand new Fairmount Fair mall:

By 1973, Fairmount Fair barely resembled this photograph, as it had been fully enclosed. One year later, an enclosed Fayetteville Mall was preparing for its August 1974 grand opening, and Shoppingtown would soon become an "air-conditioned garden mall with live trees and live flowers." (Syracuse Herald-American, August 31, 1975) True to their suburban copycat schedule, by advocating an outdoor pedestrian mall with trees and grass, downtown leaders and merchants were pursuing a shopping mall model outdated by twenty-five years. Granted, in some respects, the outdoor mall could also have been considered visionary, as the open-air "lifestyle center" would rise to popularity in another 25 years. But city leaders had neither the time nor the funds to create the pedestrian mall experience they had seen in Ottawa a decade earlier:

What they decided upon was perhaps the most unabashed—and unsuccessful—quick-fix solutions in downtown Syracuse history: a DIY pedestrian mall.

The real shame of this "famous failure" (as so noted in an August 17, 1987 Post-Standard article) was not that City Council member Ronald Monsour was actually in the minority opinion (only 2 voted against) when he stated "I don't think trees should be placed in the streets" (Post-Standard, May 7, 1974), not that a city plagued by litter problems would add 44 new receptacles to "become a catch-all for cigarette butts and debris" (Councilman-at-large James Tormey, Jr.—the other dissenting vote—quoted in Post-Standard, July 4, 1974), not that the planters were installed in bus lanes, "effectively prohibit[ing] extensive bus use of the curb traffic lanes," (Post-Standard, May 25, 1974), not David Michel stating "he does not regard the planters—even though they are in the street—as a traffic hazard...the only real danger, as Michel sees it, is someone, who has had too much to drink, driving down South Salina Street in in the predawn hours and not seeing the planters" (Post-Standard, May 25, 1974), not that Dan Sutton, president of Sutton Real Estate, acknowledged "the controversy of the planters, if nothing else, has brought many people into downtown to observe them and business has benefited" (Post-Standard, July 16, 1974), not that city council voted 5-4 to keep the planters after an initial 60-day trial period, not that seven blue-domed kiosks for posters and flyers (i.e. sources of additional litter) were installed on the sidewalk to join the planters in a "street furniture" program, despite "no one is sure who will take care of them" (Post-Standard, June 12, 1974), not that the Downtown Promotion Committee requested that during the holiday season, the planters be moved from the sides of South Salina Street and lined up down the center of the street, "with evergreens and decorated appropriately for the Christmas season" (Post-Standard, October 12, 1974), not that the City Council had to be told by Fire Chief Thomas O'Hanlon that doing so would be a fire hazard, not that they were hauled to "urban renewal-owned land at South Salina Street and West Onondaga Streets" shortly thereafter, never to be heard of again, but that the core idea behind the project was absolutely correct: Syracuse needed a beautification project.

Forget the litter or landscaping, the beautification that Syracuse required then—as now—involves a massive closet cleaning of the quick-fix plans and outdated ideas that have been hoarded for decades. Thirty years after skybridges failed to revitalize downtown, why are some still considering pairing "an enclosed glass walkway above the sidewalk" with the convention center or a (potentially) restored Hotel Syracuse? Have we held on to the 1970s skybridge plan because we think it will come back into style? Look great on Syracuse once downtown gets in shape? When the skybridge project was first announced back in early 1976, the Post-Standard editorial board admitted skepticism, but figured it couldn't be worse than the previous downtown innovation:

By the 1960s, the city of Syracuse had dismantled much of what had been built in the 1920s: Strand Theater, RKO Keith's, and the May 15, 1923 Syracuse Herald editorial declaration of the "hope that the city has now heard the last proposal from any source for the erection on our park lands of structures that have no place there." (In 1961, city leaders and residents debated building the new Southwest High School (Corcoran) in Onondaga or Kirk Park.) By the 1970s, the city of Syracuse had dismantled much of what had been built in the 1960s: Strand Parking Garage, every memory of the Corcoran/Onondaga Park controversy (in 1971, the Syracuse Board of Education declared Burnet Park an ideal site for Fowler High School), and the Texture Program.

The Texture Program, which suggested focusing on "small-in-themselves" projects for downtown Syracuse, soon became a major component of 1960s city planning. In July 1963, Texture committee members traveled to Ottawa with Mayor Walsh and city council members to view the Sparks Street Mall (Post-Standard, July 28, 1963). At the height of the protests regarding the 15th Ward destruction in October 1963, the Texture Committee tagged along with Mayor Walsh (in a travel party totaling "33 strong") on a "town-planning fact-finding mission to Europe" (Post-Standard, October 11, 1963). It's not quite clear what texture the Texture Committee added to the city during the decade, other than "MDA Texture Committee chairman Winston Rodormer's progress report point[ing] to tree planting and placing of seats in Vanderbilt Square between S. Salina and S. Warren Streets and construction of a courtyard and park of the northeast corner of the Hotel Syracuse" (Post-Standard, December 28, 1963) and hard feelings.

Mentions of the Texture Committee disappeared from newspapers by late 1960s, much like the shoppers in downtown Syracuse itself. After spending a decade in rebuilding mode only to end up in further decline, the city found itself in full-blown panic mode. As their veteran players left to join up the suburban competition, the next quick-fix plan seemed obvious:

In the late 1950s, then-Mayor Anthony Henninger...recommended Salina Street be turned into a mall, with grass and trees and walkways.

Merchants were chilly to the idea. "No grass or trees on Salina Street" was their near-unanimous response.

Lacking excitement, the street slowly decayed—and with it, the city.

...

And then a few years ago, Salina Street merchants awoke one morning and saw rusty nails being driven into the coffin that was their street.

...

Now downtown merchants don't object to trees or grass being planted on Salina Street. Many are proponents of the mall Mayor Henninger proposed in the 1950s.

"If that mall won't be in our future, we'll be in trouble," argued [Malcolm] Sutton.

(Post-Standard, April 26, 1973)

The mall Mayor Henninger proposed in the 1950s sounds very much like a replica of the then-brand new Fairmount Fair mall:

|

| via NYCO |

By 1973, Fairmount Fair barely resembled this photograph, as it had been fully enclosed. One year later, an enclosed Fayetteville Mall was preparing for its August 1974 grand opening, and Shoppingtown would soon become an "air-conditioned garden mall with live trees and live flowers." (Syracuse Herald-American, August 31, 1975) True to their suburban copycat schedule, by advocating an outdoor pedestrian mall with trees and grass, downtown leaders and merchants were pursuing a shopping mall model outdated by twenty-five years. Granted, in some respects, the outdoor mall could also have been considered visionary, as the open-air "lifestyle center" would rise to popularity in another 25 years. But city leaders had neither the time nor the funds to create the pedestrian mall experience they had seen in Ottawa a decade earlier:

|

| "Sparks Street Mall, Ottawa in the 1960s," via reinap on flickr |

What they decided upon was perhaps the most unabashed—and unsuccessful—quick-fix solutions in downtown Syracuse history: a DIY pedestrian mall.

|

| from Post-Standard, May 25, 1974 (notes added) |

|

| from Post-Standard, July 16, 1974 |

In downtown Syracuse federal and state urban renewal funds are being utilized to install "planters" containing trees and bushes in South Salina Street—making it narrower and posing potential driving hazards.

Costing about $52,000, the project is under the direction of Commissioner of Urban Improvement David S. Michel.

It involves placing 44 "planters" ranging in size from four feet square, upwards, and of varying height, right in the street proper. The "planters" are filled with trees and bushes.

The objective, he said, is to beautify Downtown Syracuse in the hope of attracting more people downtown. The project was approved on a 60-day trial basis by the Common Council, Michel asserted.

Multiple planters of varying sizes are grouped together in clusters, and placed in the curb on both sides of the street. This effectively reduces the driving area in the streets by two lanes.

...

Michel said each planter costs about $1,000, and the trees used in them $150 each. That produces, he said, a total cost of about $52,000, which, he stated, is all federal and state money, with no city funds involved. The trees used in the planters, he said, are mainly crab apple and hawthorn and juniper bushes. (Post-Standard, May 25, 1974)

The real shame of this "famous failure" (as so noted in an August 17, 1987 Post-Standard article) was not that City Council member Ronald Monsour was actually in the minority opinion (only 2 voted against) when he stated "I don't think trees should be placed in the streets" (Post-Standard, May 7, 1974), not that a city plagued by litter problems would add 44 new receptacles to "become a catch-all for cigarette butts and debris" (Councilman-at-large James Tormey, Jr.—the other dissenting vote—quoted in Post-Standard, July 4, 1974), not that the planters were installed in bus lanes, "effectively prohibit[ing] extensive bus use of the curb traffic lanes," (Post-Standard, May 25, 1974), not David Michel stating "he does not regard the planters—even though they are in the street—as a traffic hazard...the only real danger, as Michel sees it, is someone, who has had too much to drink, driving down South Salina Street in in the predawn hours and not seeing the planters" (Post-Standard, May 25, 1974), not that Dan Sutton, president of Sutton Real Estate, acknowledged "the controversy of the planters, if nothing else, has brought many people into downtown to observe them and business has benefited" (Post-Standard, July 16, 1974), not that city council voted 5-4 to keep the planters after an initial 60-day trial period, not that seven blue-domed kiosks for posters and flyers (i.e. sources of additional litter) were installed on the sidewalk to join the planters in a "street furniture" program, despite "no one is sure who will take care of them" (Post-Standard, June 12, 1974), not that the Downtown Promotion Committee requested that during the holiday season, the planters be moved from the sides of South Salina Street and lined up down the center of the street, "with evergreens and decorated appropriately for the Christmas season" (Post-Standard, October 12, 1974), not that the City Council had to be told by Fire Chief Thomas O'Hanlon that doing so would be a fire hazard, not that they were hauled to "urban renewal-owned land at South Salina Street and West Onondaga Streets" shortly thereafter, never to be heard of again, but that the core idea behind the project was absolutely correct: Syracuse needed a beautification project.

Forget the litter or landscaping, the beautification that Syracuse required then—as now—involves a massive closet cleaning of the quick-fix plans and outdated ideas that have been hoarded for decades. Thirty years after skybridges failed to revitalize downtown, why are some still considering pairing "an enclosed glass walkway above the sidewalk" with the convention center or a (potentially) restored Hotel Syracuse? Have we held on to the 1970s skybridge plan because we think it will come back into style? Look great on Syracuse once downtown gets in shape? When the skybridge project was first announced back in early 1976, the Post-Standard editorial board admitted skepticism, but figured it couldn't be worse than the previous downtown innovation:

The Post-Standard is all in favor of making the central business district the most attractive shopping center in Central New York. The latest plan is far better than the flower planters which once obstructed traffic and much more attractive than than the ugly concrete cones now smeared with aging posters flapping in the wind. (April 2, 1976)Based on the tone of this editorial, skybridges sound as if they were purchased off the final clearance rack of one of the downtown department stores fleeing for the suburbs. If we are going to dig out advice from the '70s collection to try on for size, how about this Syracuse Herald-American column by Mario Rossi from December 18, 1977?

Somewhere along the line maybe it will begin to dawn on some of our city fathers and civic leaders that if downtown Syracuse is really to be fully revitalized, the principal ingredient of many that will be needed in the formula will be imagination.Unfortunately, this commentary from the year of leisure suits is still current today. But one hopes that with over three decades to contemplate the problem, the answer will never again come in the form of a quick-fix solution.

Or creativity, if you will.

The old hackneyed ideas no longer will work. The stop gap measures won't either. And the half-way approaches will prove as useless as they have in the past.

We need something dramatic, far-reaching, exciting—something that will literally captivate shoppers and tourists and make them want to come to downtown—in droves.

Tuesday, May 25, 2010

May 15, 1923

"One of the strangest of all strange things is the unwillingness of some people to learn anything from the lessons of experience."—from a Syracuse Herald editorial, May 15, 1923

Earlier this month, Onondaga County Executive Joanie Mahoney said she wished to revisit the possibility of renovating the Hotel Syracuse and using the downtown landmark as the convention center hotel.

The first comment in reply to Sean Kirst's related column about the topic (and as noted by NYCO in this blog's comments): "The best way to make the Hotel Syracuse the convention center's hotel, is to build an enclosed glass walkway above the sidewalk."

In other words, a skybridge!

Not that this is surprising: skybridges and convention center are more married in the Syracuse public mind than CenterState CEO, who in their single days had been promoting skybridges since the '70s. Perhaps those who reintroduce skybridges to the conversation are not so much recycling a three-decade old proposition, but rather exploring an idea that they feel has never been pursued to its fullest potential. After all, the skybridges of the '70s connected the defunct Syracuse Mall to a parking garage, not a fully restored Hotel Syracuse to the Convention Center!

Or is "skybridge" just the answer that is most quick and convenient, the very two post-WWII buzzwords that contributed to the downfall of downtown in the first place?

****

As a recent Dick Case column reminds us, the Hotel Syracuse had its share of difficulties prior to and during its construction. The hotel was not the only city project stuck in a holding pattern at the time. Along with the railroad, another particularly contentious dispute had the movers and shakers of 1920s Syracuse choosing sides. The fight regarding the construction of Nottingham Junior High School pitted Percy Hughes, Superintendent of Syracuse schools, against two mayoral administrations, prominent citizens, and the Syracuse Herald. While all parties agreed upon the necessity of a new school for the rapidly-growing city, only Hughes and the Syracuse Board of Education advocated locating the building in Thornden Park:

Mayor Farmer immediately voiced his opposition, stating "I do not believe parks should be sacrificed in this way." (Syracuse Herald, May 11, 1921). Joining Farmer in the outrage were city aldermen:

A.E. Nettleton:

Salem Hyde:

Donald Dey:

Syracuse Herald publisher Edward H. O'Hara saw the conflict in terms of one that would come to haunt Syracuse for years to come: the quick-fix versus long-term planning solution.

Mayor John Walrath, who came to office in 1922, also took a stand against building the school in Thornden Park, insisting instead that it be located on the corner of Fellows Ave and Harvard Place. Walrath made "appeals to the effect that he was 25 years ahead of his time" (Syracuse Herald, April 15, 1923), a point echoed by the Syracuse Herald editorial page:

Faced with a stalemate as the city's schoolchildren population continued to grow, Superintendent Hughes and the Board of Education relented, never endorsing the Fellows Place site, but simply agreeing to turn decision over to the mayor. Upon declaring the final location for the school, Mayor Walrath again reiterated his visionary outlook:

Little did Mayor Walrath know that 25 years after making this statement about being 25 years ahead of his time, Syracuse would be at the would be at the start of the post-WWII suburban housing boom. In the two years of the school location dispute, the city added more residents, thus requiring the school in the first place (although the city versus suburbs debate had already started, demonstrated by this side-by-side pair of advertisements):

In the two years it took City of Syracuse to decide the location of one public housing apartment building in the late 1940s, the developers of Levittown, New York were building single family homes at a rate of thirty a day. By the time similar post-war communities sprung up outside of Syracuse, along with companion shopping centers, supermarkets, etc., city leaders who wished to "build for the future" felt as if they had to catch up with the suburbs, going so far as to declare the city center itself irrelevant for residential living:

Just as a park is a park, a downtown is a downtown. But by city leaders declaring their downtown essentially obsolete, any "building for the future" automatically became a mimicry of the suburbs. How could the city ever again be 25 years ahead of its time when it was already 25 years behind the model of what it aspired to be? Thus, by the early 1960s, the Metropolitan Development Association suggested that the future of downtown might be shaped by a series of quick-fix solutions:

One might think the post was a ball of fire because you don't suggest redecorating the house while it is burning to the ground. But, rather, quite the opposite:

The "texture" theory, according to Bartlett, "may be defined as bit-by-bit reactions that add up to an overall on the part of an individual." (Post-Standard, August 13, 1961). Bartlett suggested "possibly identifying the location of broken sidewalks that ought to be repaired and curbs that should be replaced...more attention-getting waste containers, consideration should be given to the use of trees or hedges to beautify off-street parking areas." Of course, texture can also be created by lumping together a patchwork of projects, creating unbalance:

These "interesting paved areas" here and "walkways and benches" there were not only adding "texture," but, as Bartlett himself stated, "bit by bit" altering individual parts of an "overall" landscape. Texture is an element of design, not the design itself. How do you know when to stop adding texture, if you have no vision for the finished product?

Perhaps when the texture is declared a safety hazard by the fire marshal and hauled away.

To be continued...

Coming soon:

May 15, 1974

"I don't think trees should be placed in the street."

Earlier this month, Onondaga County Executive Joanie Mahoney said she wished to revisit the possibility of renovating the Hotel Syracuse and using the downtown landmark as the convention center hotel.

The first comment in reply to Sean Kirst's related column about the topic (and as noted by NYCO in this blog's comments): "The best way to make the Hotel Syracuse the convention center's hotel, is to build an enclosed glass walkway above the sidewalk."

In other words, a skybridge!

Not that this is surprising: skybridges and convention center are more married in the Syracuse public mind than CenterState CEO, who in their single days had been promoting skybridges since the '70s. Perhaps those who reintroduce skybridges to the conversation are not so much recycling a three-decade old proposition, but rather exploring an idea that they feel has never been pursued to its fullest potential. After all, the skybridges of the '70s connected the defunct Syracuse Mall to a parking garage, not a fully restored Hotel Syracuse to the Convention Center!

Or is "skybridge" just the answer that is most quick and convenient, the very two post-WWII buzzwords that contributed to the downfall of downtown in the first place?

****