A Syracuse tale of city, suburbs, public housing, arterial highways...and bowling:

Thursday, March 31, 2011

Friday, March 18, 2011

March 18, 1915

As Syracuse approaches the 75th anniversary of the elevation of the railroad tracks, this blog will revisit the history leading up to this most divisive decision. Call it (Dis)Union Station, if you will.

By 1915, Syracuse still had no answer to the Grade Crossing dilemma. It had, however, “reached the conclusion that one solution had been found that eliminates the disadvantages of all other suggested solutions” (Syracuse Herald, March 18, 1915). The proposal: run the trains through a 6,000-foot long tunnel underneath the eastern section of the city.

Yes, this was a far cry from the track elevation plan that had seemed inevitable just two years earlier during the Schoeneck administration. But 1913 brought the election of a new mayor, president of Will & Baumer Louis Will, as well as an in-depth study by the Grade Crossing Commission, which submitted seven potential plans for grade crossing elimination to Mayor Will shortly after he took office. The plans, as described in a February 6, 1914 Post-Standard article, are summarized in the chart below:

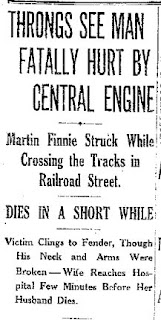

Will, the city’s first Progressive mayor, had placed Grade Crossing Abolition at the top of his campaign platform, stating “any future city administration will be remiss in its duty if it fails to use every means in its power to accomplish the abolishment of [railroad] traffic through our city” (Syracuse Herald, October 16, 1913). Granted, the Republican and Democratic candidates had as well; the problem had now been in the headlines for almost 15 years. East Washington Street continued to be scene of gruesome accidents. As the number of automobiles increased, traffic jams also became a major concern, as Will addressed in a speech to voters:

Yet as the years passed, the option that once had been most readily considered, the solution that had been put in place in other upstate cities such as Rochester and Schenectady, fell more out of favor with Syracusans. Despite actual fatalities cause by grade crossings, Mayor Will spoke of the death that could befall Syracuse if elevated tracks were allowed in the city:

Residents from all sides of Syracuse came out in protest against track elevation: the North Side against elevated New York Central tracks that would act as another barrier in addition to the canal, the South Side, against elevated Lackawanna tracks on embankments that would depreciate property values, and the East Side against the railroad’s plan to “open Van Buren Street, declaring that it will practically shut off the Raynor tract and make the district far from desirable for residential purposes” (Syracuse Herald, July 31, 1914). In the face of this widespread opposition, the City Planning Commission issued the following statement:

Though the Syracuse Herald editorial page offered this observation the next day:

***

Louis Will had run on the “the efficiency ticket,” promising “a vote for efficiency is a vote for better methods.” When New York Central engineers seemed amenable to considering track depression as an alternative solution (tracks would be built in the abandoned Erie Canal bed), Will—in disagreement with the Grade Crossing Commission—rejected the proposal as unacceptable:

The efficient plan was the one that could be started immediately, and Will contended that such a plan existed:

Will favored what would later be come to known as the Northern Route: the tracks would skirt the city to the north, with a passenger station on Spencer Street, by Onondaga Lake. Will contested the railroad's claim that the disadvantage of the plan was the non-central location of the station:

The mayor argued that New York Central rejected the plan outright due to their own corporate and financial interests:

Perhaps this gives some indication as to why Will championed the underground tunnel suggestion. The plan certainly didn’t seem more efficient in terms of time, as digging a tunnel that would begin “east of the city, somewhere in the vicinity of Greenway Avenue...run under Teall Avenue, Lincoln Park, Oak and James Street” would probably take at least the five years required to secure canal beds. Nor was it very practical, as there were questions about tunnel ventilation, and the soil, which “throughout the eastern section of the city would not lend itself advantageously to the tunneling work...it is a loose shale and elaborate supports would have to be constructed.” (Syracuse Herald, March 19, 1915). Yet the plan was efficient in one specific area: Mayor Will asserting his autonomy from the New York Central Railroad and the Grade Crossing Commission. Mayor Will did not wish to “appeal to the [railroad’s] sense of justice and good” as city leaders had fifteen years earlier. Even when the Grade Crossing Commission officially approved a plan using the canal bed on April 23,1915, with the intent of immediately entering a contract with the New York Central Railroad to construct this new route, Will made clear that he would not give up on tunnel proposal:

One month later, he still held firm:

In another ten years, Will would let the city in on his plan, when he became the driving force behind the group of prominent Syracuse businessmen and residents determined to keep elevated structures out of the city. Even more importantly, the Future Syracuse Committee, formed in 1923, wanted the decision of grade crossing elimination to be made directly by the voters. Because as Will realized during his final weeks in the mayor’s office in 1915, there was a great dispute of opinions between the Mayor, the Grade Crossing Commission, the Railroads and the people of Syracuse:

And so matters did remain as the same. But as Will may have realized, so too would those making the decisions on these matters. The members of the Grade Crossing Commission—including Will’s own brother, Albert—had remained unchanged since their appointment in 1911 (with the exception of Alan Fobes, who stepped down after one year, replaced by Thomas Meachem). Of particular concern must have been Grade Crossing Commissioner Engineer Henry C. Allen, who started with the crossing elimination project under the McGuire administration as city engineer. When Will replaced him upon his own election to office, the Grade Crossing Commission immediately appointed Allen as their chief engineer. Now, as Will concluded his time as mayor (he did not run for reelection), Allen appeared poised to serve as both City Engineer and Grade Crossing Commission Engineer simultaneously under the incoming (Republican) Walter Stone administration. With less than two months left in office, Will not only successfully blocked Allen's plans to elevate the Lackawanna tracks, he issued a critical statement against Allen and the Grade Crossing Commission:

With less than six weeks left in office, Will scored a final victory: the Grade Crossing Commission would hire an outside expert to conduct a study of Syracuse grade crossings. But in another decade's time, the most prominent outside voice in the grade crossing dilemma would be Will himself.

1. After making this declaration, Will discovered the 1899 Seaman study done under Mayor McGuire, which had supported elevation of the New York Central tracks, but not the Lackawanna tracks.↩

2. The Grade Crossing Commission insisted that "it would be impossible to get the Lackawanna and New York Central railways to use the same station." When Will expressed an interest in hiring the expert who eliminated grade crossings in Chicago, Grade Crossing Commission president Alexander T. Brown said "practically all the tracks in that city are elevated and that if the expert were brought here he would probably approve the elevating plans." Will immediately shot back that "as he understood it, there wasn't a railway station in Chicago that wasn't occupied by more than one railway." (Syracuse Herald, November 13, 1915) ↩

By 1915, Syracuse still had no answer to the Grade Crossing dilemma. It had, however, “reached the conclusion that one solution had been found that eliminates the disadvantages of all other suggested solutions” (Syracuse Herald, March 18, 1915). The proposal: run the trains through a 6,000-foot long tunnel underneath the eastern section of the city.

Yes, this was a far cry from the track elevation plan that had seemed inevitable just two years earlier during the Schoeneck administration. But 1913 brought the election of a new mayor, president of Will & Baumer Louis Will, as well as an in-depth study by the Grade Crossing Commission, which submitted seven potential plans for grade crossing elimination to Mayor Will shortly after he took office. The plans, as described in a February 6, 1914 Post-Standard article, are summarized in the chart below:

|

| Click to enlarge |

|

| Syracuse Herald, September 14, 1912 |

The switching of trains by means of switches located between Clinton and Franklin Streets frequently cuts off these streets for five and ten minute periods, and these switches, located as they are (causing two streets of such great importance to be shut off almost hourly), should never have been permitted at these points and should be removed. (Syracuse Herald, October 16, 1913).

Yet as the years passed, the option that once had been most readily considered, the solution that had been put in place in other upstate cities such as Rochester and Schenectady, fell more out of favor with Syracusans. Despite actual fatalities cause by grade crossings, Mayor Will spoke of the death that could befall Syracuse if elevated tracks were allowed in the city:

“If the New York Central lines were elevated through the city that would mean that the Lackawanna tracks would also be elevated,” said Mayor Will. “There would be two unsightly banks running through the heart of the city and the city would be killed.” (Syracuse Herald, June 11, 1914)

|

| The Delaware, Western & Lackawanna Railroad map, 1922 |

“We, the members of the Commission, are agreed that in effect and appearance, no matter how sightly and well-designed an elevated structure may be, it will always be a barrier and affliction. If any other solution is practicable, elevation should not be tolerated.” (Syracuse Herald, July 28, 1914)

Though the Syracuse Herald editorial page offered this observation the next day:

The members of the City Planning Commission are agreed that the proposed elevation of the Lackawanna tracks in this city would “always be a barrier and an affliction.” It would be an affliction richly deserved, however, if the city meekly puts up with it.” (Syracuse Herald, July 29, 1914).

***

|

| Syracuse Herald, October 19, 1913 |

The mayor says that, as he figures it, it will be five years before the canal bed is abandoned and that it would probably mean years of litigation when the city set about to secure the abandoned land. He is against any plan for ending the grade crossing nuisance which is going to take that length of time. (Syracuse Herald, November 24, 1914).

The efficient plan was the one that could be started immediately, and Will contended that such a plan existed:

Mayor Will said that if the commissioners and the railway authorities would agree upon the plan to have the railway tracks pass through the center of the city on the north there is no good reason why work of doing away with the grade crossings could not begin tomorrow. He is against any policy which will interfere with the beginning of the work. (Syracuse Herald, November 24, 1914).

Will favored what would later be come to known as the Northern Route: the tracks would skirt the city to the north, with a passenger station on Spencer Street, by Onondaga Lake. Will contested the railroad's claim that the disadvantage of the plan was the non-central location of the station:

Mayor Will said he believe he could prove if he had time to gather statistics that 75 percent of the cities of the United States have their railway stations a mile or more distant from the center of the city. He sees little to the argument that a railway station must be near the center of the city. (Syracuse Herald, November 24, 1914).

The mayor argued that New York Central rejected the plan outright due to their own corporate and financial interests:

Mayor Will said that he pointed out to the officials, among the [New York Central Railroad] president A.H. Smith, that extending tracks north of the city would allow the trains to run at full speed. Much time could be gained over that which it takes trains to proceed through the city at present.

“Of course what the Central wants,” said Mayor Will, “is to shorten their trackage and still be allowed to run at full speed through the city.” (Syracuse Herald, June 11, 1914)

Perhaps this gives some indication as to why Will championed the underground tunnel suggestion. The plan certainly didn’t seem more efficient in terms of time, as digging a tunnel that would begin “east of the city, somewhere in the vicinity of Greenway Avenue...run under Teall Avenue, Lincoln Park, Oak and James Street” would probably take at least the five years required to secure canal beds. Nor was it very practical, as there were questions about tunnel ventilation, and the soil, which “throughout the eastern section of the city would not lend itself advantageously to the tunneling work...it is a loose shale and elaborate supports would have to be constructed.” (Syracuse Herald, March 19, 1915). Yet the plan was efficient in one specific area: Mayor Will asserting his autonomy from the New York Central Railroad and the Grade Crossing Commission. Mayor Will did not wish to “appeal to the [railroad’s] sense of justice and good” as city leaders had fifteen years earlier. Even when the Grade Crossing Commission officially approved a plan using the canal bed on April 23,1915, with the intent of immediately entering a contract with the New York Central Railroad to construct this new route, Will made clear that he would not give up on tunnel proposal:

The idea of tunneling as the solution of the grade crossing elimination problem has not been abandoned by Mayor Will despite the fact that the members of the Grade Crossing Commission have reported adversely upon it and have proceeded to endorse another plan recommended by [Grade Crossing Commission Engineer] Henry C. Allen, providing for a depressed route through the city.

Accompanied by City Engineer Wooley, Deputy City Engineer Palmer and Commissioner Mather of the Department of Public Works, Mayor Will spent some time today looking over the surface of the land in that section of the city where it is proposed to build the tunnel.

Deputy City Engineer Palmer has been busy drawing contour maps of the vicinity, and the mayor is evidently determined to investigate the project thoroughly before endorsing any other plan. (Syracuse Herald, April 29, 1915).

One month later, he still held firm:

Officials of the Grade Crossing Commission declined today to make any comment on the Mayor’s statement in which he charged that they were wedded to the canal route as a solution for the grade crossing problem. In the statement, the Mayor again went on record in favoring of his tunneling plan.

“If he had plans which are the most logical why don’t [sic] he let us in on the secret?” asked Henry C. Allen, chief engineer. He said that he did not intend to get into any dispute with the Mayor. (Syracuse Herald, May 26, 1915).

In another ten years, Will would let the city in on his plan, when he became the driving force behind the group of prominent Syracuse businessmen and residents determined to keep elevated structures out of the city. Even more importantly, the Future Syracuse Committee, formed in 1923, wanted the decision of grade crossing elimination to be made directly by the voters. Because as Will realized during his final weeks in the mayor’s office in 1915, there was a great dispute of opinions between the Mayor, the Grade Crossing Commission, the Railroads and the people of Syracuse:

FOR THE GOOD OF THE CITY

Mayor Will has acted wisely in taking a firm stand against the settlement of the Lackawanna’s grade crossing problem proposed by the railroad company and acquiesced in by the city’s Grade Crossing Commission. If he succeeds in blocking this plan to build a huge concrete embankment through a populous section of the city, it will be one of the most important acts of his administration.

In this matter, as the Mayor says, too much deference has been paid to the railroad’s point of view. The city’s interests come first, and no plan that involves such injury to those interests as this track elevation plan does should be accepted without at least first making sure that no other solution is possible.

Other cities have solved this problem in a manner which did not sacrifice their interests to those of the railroads. Why should it be impossible for Syracuse do to so? The union station proposition was accepted in Utica. Evidently we need to take some lessons from Utica on how to deal with the railroads.

The Mayor’s suggestion that an outside expert be called in to look over the situation is a good one. Certainly no effort should be spared to provide the right solution to a problem which is of such vital importance to the future of the city. And rather than accept the wrong solution, it would be better to let matters remain as they are. (Syracuse Herald editorial, November 11, 1915).

And so matters did remain as the same. But as Will may have realized, so too would those making the decisions on these matters. The members of the Grade Crossing Commission—including Will’s own brother, Albert—had remained unchanged since their appointment in 1911 (with the exception of Alan Fobes, who stepped down after one year, replaced by Thomas Meachem). Of particular concern must have been Grade Crossing Commissioner Engineer Henry C. Allen, who started with the crossing elimination project under the McGuire administration as city engineer. When Will replaced him upon his own election to office, the Grade Crossing Commission immediately appointed Allen as their chief engineer. Now, as Will concluded his time as mayor (he did not run for reelection), Allen appeared poised to serve as both City Engineer and Grade Crossing Commission Engineer simultaneously under the incoming (Republican) Walter Stone administration. With less than two months left in office, Will not only successfully blocked Allen's plans to elevate the Lackawanna tracks, he issued a critical statement against Allen and the Grade Crossing Commission:

Mayor Will today issued a broadside against the Grade Crossing Commission and Henry C. Allen, the commission's chief engineer. He first declared that Corporation Counsel Stilwell would refuse to approve any contract calling for elevation of the Lackawanna tracks through the city and then detailed his criticisms of Mr. Allen and the commission.

The chief criticisms can be stated as follows:

First—That the plan to elevate represents the conclusions of the railway companies and one man, Mr. Allen, and that the problem is too important to be passed upon finally but one representative of the city.

Second—That Mr. Allen, and the commission have accepted the plan of the railroad to elevate in order to avoid a fight with the company and that if the commission and Mr. Allen had dared "lock horns" with the railways three or four years ago the whole crossing problem would have been settled advantageously to the city before this time.

Third—That the city should not be committed to the elevating plan until some impartial expert has gone over the whole situation. The Mayor holds that no expert has been called in for consultation yet.1

Fourth—That the companies accepted the union station proposition in Utica and other cities. Why not in Syracuse? 2

Fifth—That it would be better to wait twenty years and get the right solution of the crossing problem than to hastily select the wrong solution.

(Syracuse Herald, November 10, 1915)

With less than six weeks left in office, Will scored a final victory: the Grade Crossing Commission would hire an outside expert to conduct a study of Syracuse grade crossings. But in another decade's time, the most prominent outside voice in the grade crossing dilemma would be Will himself.

1. After making this declaration, Will discovered the 1899 Seaman study done under Mayor McGuire, which had supported elevation of the New York Central tracks, but not the Lackawanna tracks.↩

2. The Grade Crossing Commission insisted that "it would be impossible to get the Lackawanna and New York Central railways to use the same station." When Will expressed an interest in hiring the expert who eliminated grade crossings in Chicago, Grade Crossing Commission president Alexander T. Brown said "practically all the tracks in that city are elevated and that if the expert were brought here he would probably approve the elevating plans." Will immediately shot back that "as he understood it, there wasn't a railway station in Chicago that wasn't occupied by more than one railway." (Syracuse Herald, November 13, 1915) ↩

Tuesday, March 1, 2011

March 1910

As Syracuse approaches the 75th anniversary of the elevation of the railroad tracks, this blog will revisit the history leading up to this most divisive decision. Call it (Dis)Union Station, if you will.

In the first decade of the twentieth century, under Mayor Fobes, Syracuse bought the land for Kirk Park, opened the Frazer playground and started work on Lincoln Park. At the time, there was a movement nationwide for increased development of open spaces for recreation, as cities became more crowded and congested. In Syracuse, of course, this meant parks that provided an escape from the noise and pollution associated with the New York Central Railroad running down Washington Street.

In 1910, another young Mayor took over City Hall. Although attorney Edward Schoeneck and former mayor James McGuire exchanged a war of words during the campaign (Schoeneck viewed his opponent, George Driscoll, as “a creature of McGuire” (Post-Standard, November 1, 1909); McGuire considered Schoeneck “weak clay in the hands of his political maker and his candidacy an affont to the citizens” (Syracuse Herald, October 20, 1909)), once elected, Schoeneck picked up the grade crossing elimination battle where McGuire had left off almost a decade earlier:

Not much had changed regarding grade crossing elimination since McGuire’s time: the grade crossing act required the railroad to pay for fifty percent of the solution, with the state and city covering the remaining half evenly. Of course, the cost of project had been revised, with the estimate increased to $4 million. Mayor Schoeneck felt “as much as Syracuse desired the removal of steam railway traffic from its streets, the city was neither able nor willing to assume a bonded debt of $1,000,000 to bring about the results” (Post-Standard, July 30, 1910).

Another difference since McGuire’s time were the scores of additional injuries and deaths that continued to be caused by grade crossings. Although the New York Central Railroad had earlier insisted they were not contractually obligated to take any action on the Washington Street tracks until 1917, repeated headlines about amputated fingers and crushed legs could be considered as bad for the corporate brand. When Schoeneck met with New York Central President W.C. Brown in April 1910, he found the railroad chief to be more “liberal” towards the grade crossing situation:

Brown and Schoeneck discussed alternative means of reimbursement for Syracuse’s share of expenses, including allowing the New York Central to buy a franchise of streetcars which would operate on East Washington Street, absolution of any costs incurred by the city associated with street closings during construction, and “the remission to the New York Central of taxes which would accrue to Syracuse as a result of the increased taxable valuation of its property here, incidental to the construction of a new station, the elevation of its tracks and other betterments and improvements.” (Post-Standard, July 30, 1910).

But it wasn’t only the expense of the project that caused unease for the Syracuse city leaders:

Almost a year after Mayor Schoeneck first met with the New York Central, the city announced that two plans that had been submitted to the railroad for consideration—essentially the same two plans that been considered twelve years earlier. The Post-Standard expected the possibility of elevated tracks might cause a “warm controversy”:

The issue may have been particularly sensitive to Schoeneck, a resident of North McBride Street. Endorsement of elevation would not only alienate constituents, but his own neighbors. As the election year continued (at the time, mayors served 2-year terms), grade crossing elimination had become the most unique of political issues: while the progress Schoeneck had made with the New York Central railroad had been the most substantial in twenty years, any public support of the West Shore Elevation plan could lose potential voters. Schoeneck, perhaps sensing this precarious position, asked the Common Council to approve the creation of a Grade Crossing Commission:

Democratic Aldermen in the Common Council voted against the ordinance to create the commission, as the Schoeneck-named commission could be in place for years. However, Alderman Patrick Cawley of the First Ward (residing at 617 Bear Street) had his own reasons for voting no:

Democratic mayoral challenger James Ludington contended that the Commission was a political maneuver to avoid a public statement on the elevation issue:

Schoeneck won re-election, serving a second term as mayor until 1913 (and later as lieutenant governor of New York from 1915-1919). By the time of the election for Syracuse’s next mayor, the issue of grade crossing elimination—more specifically, track elevation—had progressed from a “warm controversy” to “the hottest municipal row in the history of Syracuse” (Syracuse Herald, March 11, 1914) . And not only would the next mayor state his opinion on the matter for the public record, he would turn the cause into a battle for Syracuse’s future.

|

| Corner of Salina and East Washington Street, October 1909 |

In 1910, another young Mayor took over City Hall. Although attorney Edward Schoeneck and former mayor James McGuire exchanged a war of words during the campaign (Schoeneck viewed his opponent, George Driscoll, as “a creature of McGuire” (Post-Standard, November 1, 1909); McGuire considered Schoeneck “weak clay in the hands of his political maker and his candidacy an affont to the citizens” (Syracuse Herald, October 20, 1909)), once elected, Schoeneck picked up the grade crossing elimination battle where McGuire had left off almost a decade earlier:

Mayor Edward Schoeneck yesterday took up the serious consideration of ways and means by which the removal of the New York Central tracks from Washington Street may be effected and a plan worked out by which scores of railroad crossings at grade may be abolished in Syracuse.

Mr. Schoeneck has had the matter under advisement for some time, according to statements made yesterday by members of his administration with whom he has discussed the question. He is said to have agreed with the declaration of Judge Irving G. Vann at the Chamber of Commerce banquet Saturday evening that the time is at hand when definite steps should be taken to secure the removal of the railroad tracks from the business center of Syracuse. (Post-Standard, March 22, 1910).

Not much had changed regarding grade crossing elimination since McGuire’s time: the grade crossing act required the railroad to pay for fifty percent of the solution, with the state and city covering the remaining half evenly. Of course, the cost of project had been revised, with the estimate increased to $4 million. Mayor Schoeneck felt “as much as Syracuse desired the removal of steam railway traffic from its streets, the city was neither able nor willing to assume a bonded debt of $1,000,000 to bring about the results” (Post-Standard, July 30, 1910).

|

| Post-Standard, May 15, 1907 |

“President Brown showed a disposition to treat the matter in a broad and liberal spirit,” said the Mayor yesterday. “From his attitude I feel confident that we will be able to solve the grade crossing problem satisfactorily without recourse to the grade crossing act.” (Mayor Schoeneck, quoted in Post-Standard, April 4, 1910).

Brown and Schoeneck discussed alternative means of reimbursement for Syracuse’s share of expenses, including allowing the New York Central to buy a franchise of streetcars which would operate on East Washington Street, absolution of any costs incurred by the city associated with street closings during construction, and “the remission to the New York Central of taxes which would accrue to Syracuse as a result of the increased taxable valuation of its property here, incidental to the construction of a new station, the elevation of its tracks and other betterments and improvements.” (Post-Standard, July 30, 1910).

But it wasn’t only the expense of the project that caused unease for the Syracuse city leaders:

It was learned that the construction of an elevated structure by the West Shore route was the basis of discussion. City Engineer [Henry] Allen, it was ascertained later, impressed upon President Brown that the street crossings, particularly at North Salina Street, must be built to mar the street as little as possible and to avoid damaging adjacent property.

It was pointed out that in the case of recent elimination of grade crossings in Schenectady, that State Street, the city’s main thoroughfare, had suffered severely in its most important part. There, the heavy, closely built elevated structure practically shuts off all overhead light from the underlying street. These points, it is understood, were made note of by Mr. Brown, who gave his assurance that the cross streets would be marred in no way by the change. (Post-Standard, April 2, 1910).

Almost a year after Mayor Schoeneck first met with the New York Central, the city announced that two plans that had been submitted to the railroad for consideration—essentially the same two plans that been considered twelve years earlier. The Post-Standard expected the possibility of elevated tracks might cause a “warm controversy”:

A decision on the two plans to be offered will be reached only after a warm controversy. Opposition to the elevation of the West Shore tracks has already been voiced by the First and Second Wards Citizen Improvement Association and the North Side Citizens Association.

...

Residents of the North Side have taken the position that elevated tracks along the West Shore route would be unsightly, and that they would form a wall dividing the city into two parts more effectually than does the Erie canal. The division, they contend, being farther to the north than the canal, would be detrimental to the development of the North Side. (Post-Standard, February 17, 1911).

| |

| former Schoeneck residence, 500 North McBride Street |

The five men who form the Grade Crossing Commission, which the Common Council authorized Mayor Schoeneck to appoint, are Alan C. Fobes, former mayor of the city; Henry H.S. Handy, president of the Chamber of Commerce; Alexander T. Brown, manufacturer, capitalist and inventor; Albert J. Will, manufacturer, and John T. O’Brien, labor representative.

The commission, under the ordinance that the Common Council adopted, authorizing its appointment by the mayor, is directed to investigate not only the physical plan of doing away with the crossings at grade, but also to take into consideration the question of the financing of the project. The commission has no authority under the ordinance to bind the city, but is directed to investigate and make report of its investigations to the Common Council (Syracuse Herald, October 18, 1911).

|

| from Schoeneck campaign ad, Syracuse Herald, October 31, 1911 |

“It is said that it is an absolute fact,” Cawley declared, “that Mayor Schoeneck and the New York Central have entered into an agreement by which the tracks of the West Shore railroad will be elevated and will in consequence, greatly damage the principal streets of the city.”

He said he understood that the plan that had been agreed on would damage James and Salina street and would cut the city in two. He referred to the elevation in Rochester as an argument against the same procedure in the city. “I am against any ordinance that is going to damage Syracuse and divide the North and the South side. We want a united city. We don’t want an elevated road over the main streets.” (Syracuse Herald, October 10, 1911)

|

| From Ludington campaign ad, Syracuse Herald, November 2, 1911 |

“If it is true that the plans for the elimination of the grade crossings have been practically agreed on, as they say they have, you have a right to know now before election what the plans are. If he has a plan that will divide the North side and the South side you have a right to know.” (Ludington, at an speech at Hoffman Hall, 303 North Salina Street, quoted in Syracuse Herald, November 1, 1911)

Schoeneck won re-election, serving a second term as mayor until 1913 (and later as lieutenant governor of New York from 1915-1919). By the time of the election for Syracuse’s next mayor, the issue of grade crossing elimination—more specifically, track elevation—had progressed from a “warm controversy” to “the hottest municipal row in the history of Syracuse” (Syracuse Herald, March 11, 1914) . And not only would the next mayor state his opinion on the matter for the public record, he would turn the cause into a battle for Syracuse’s future.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)